Like basically every restaurant in Philly, Center City’s Good Dog Bar turned to outdoor dining to keep the business alive during the pandemic. In March 2020, they shut down with a basement full of beer for St. Patrick Day festivities and they didn’t re-open for in-person dining until June, when the City eased outdoor dining restrictions.

It started with sidewalk seating, which has long been allowed in Philly, eventually building a structure using barrels and wood to expand into the nearby parking lane. But the restaurant’s streetery became more than a tool for survival. It was fun.

Jeff Kile, Good Dog’s general manager, recalls joking with patrons while waiting tables in his snow boots. The structure, affectionately nicknamed the “doghouse” on the company’s social media, allowed people to finally bring their dogs to Good Dog. For Halloween, they held a dog costume contest.

“It was nice to see people outside,” says Kile. “It gives us more outdoor space for people to enjoy.”

Today, the once thriving streetery is down to just three tables, each seating four, surrounded by water-filled barricades. Gone are the roof strung with fairy lights and the barrels lush with greenery. In an effort to comply with the Streets Department’s Outdoor Dining Program, implemented in November 2022, the restaurant had to halve its seating outside, remove features that use electricity and make numerous other changes — all at a steep cost.

After the city saw roughly 800 streeteries open at the height of Covid, regulations became so onerous that only 13 restaurants currently have active streetery licenses — a decline that has both elected officials and the public asking: What the hell happened to Philly’s streeteries?

City Council, which is scrambling to fix the issue before another outdoor dining season comes and goes, could look to New York City and Pittsburgh for solutions.

Wading into the red tape

Philly’s streetery program, like those in many cities, has haphazard origins. The City quickly implemented a program during the first summer of Covid, with few regulations to help restaurants survive. At the time, there were four streetery options: sidewalk cafés, streeteries in parking lanes, use of adjacent lots and road closures. Each required separate permitting processes, but the City expedited reviews. In 2020, new sidewalk cafés and streeteries were getting approved in as quickly as three days.

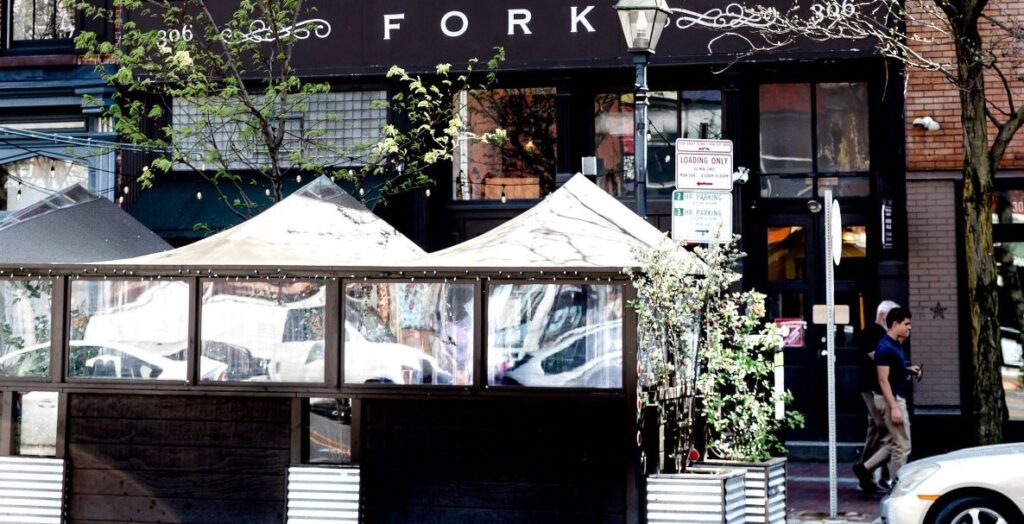

“We really appreciate how quickly the administration was able to act to enable us to be able to do this and to align with the state so that we could sell alcoholic beverages,” says Ellen Yin, founder and co-owner of High Street Hospitality Group and 2023 winner of the James Beard Award for Outstanding Restaurateur. Her restaurants Fork and a.kitchen+bar had streeteries during the pandemic. “For many people, that probably saved them.”

“The biggest complaint we’ve heard from the owners is that the process isn’t streamlined. It’s cumbersome. It’s confusing. There’s too many City departments to talk to and places to go.” — Councilmember Rue Landau

In 2022, the City released its new outdoor dining regulations, intended to help make the streeteries safer. Requirements for the strength and type of barriers can help protect diners from passing cars. Water or concrete would replace sand in weighted barriers, which officials in other cities say helps keep pests like rats at bay.

Under the new regulations, there are two types of licenses: one for sidewalk cafés and one for streeteries. The sidewalk café license allows restaurants to set up tables on the sidewalk outside their restaurant. The streetery license is for those looking to occupy parking lanes.

But the regulations for the outdoor dining program are an example of the worst kind of Philly bureaucracy. Restaurant owners have said the process is confusing and requires approvals from too many City departments. It’s also expensive. Good Dog Bar invested $30,000 into the various iterations of its streeteries.

Streeteries must have crash barriers to protect patrons from cars. They need to be five feet from manhole covers; 15 feet from fire hydrants; and 20 feet from intersections without stop signs. Those at intersections with stop signs or lights must be 30 feet away, making it nearly impossible for corner restaurants to operate streeteries. Structures must be a minimum height of seven feet and a maximum height of 10 feet. They must be ADA compliant. Many restaurants have hired architects to create plans that comply.

Restaurants need to get approval from the Streets Department, the Department of Licenses and Inspections and the Art Commission. The Streets Department grants the streetery right-of-way; L&I issues building permits and the streetery license; the Art Commision helps approve designs. Those outside of streetry-by-right districts have to contact their district council member to get a City ordinance allowing them to operate.

Many were not allowed to extend beyond the bounds of the restaurant’s property, even if they had permission from a neighbor, like what Good Dog Bar secured when it operated its original streeteries. This problem is known to restaurant owners as the adjacency issue.

“The streeteries that were covered or roof streetries — none of them, or very few of them, would have received a permit as they were under the new regulations,” says Ben Fileccia, senior vice president of strategy and engagement with the Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association. “That means people had to tear down their existing structure and once they were down, when they saw the list of items required to rebuild, a lot of them decided they didn’t want to do it. They already spent too much money on the first one.”

Yin is one restaurant owner who had to dismantle her streeteries because they didn’t comply with the regulations. Her setup at Fork, which she felt was “really special,” included wooden walls, tented roofs and planters with shrubs and small trees. It didn’t fit the new regulations, so she submitted a new plan, drafted by architects. She believes it didn’t get past Streets Department review mostly because it’s on Market Street, which is technically a state highway.

For a.kitchen+bar, she deconstructed her streetery and has spent the last few years trying to get a design approved and built. In 2022, she got a design approved, but was told the regulations would be changing again soon, so she didn’t build it. Instead, she left up a temporary structure and received a fine.

This year, she started the process for a.kitchen+bar in January, but when she finally reached a builder they said they wouldn’t be able to build it until September — when outdoor dining season is almost over. This is after hiring architects and working with multiple city departments to get approval. When asked, she did not specify how much the process has cost her.

“None of it seems unreasonable, but it just takes a really long time. We even paid the expedited review and we still couldn’t get it done,” she says.

A modular streetery system

On a warm, but cloudy day in New York’s Lower East Side, the streetery at Sunday to Sunday café is alive with patrons. The owner, Gurpreet Singh, leans against the wall of his structure, which is strung with battery-powered lights and a red-and-white striped awning that looks like a circus tent. Across the street is another streetery. Around the block, yet another.

New York has kept its outdoor dining scene alive because they’ve made things simple — and given restaurants time to comply with regulations. Rather than introduce a series of confusing regulations and require restaurants to comply, New York created a pilot program that allowed restaurants to keep their streeteries after the pandemic while the city government got feedback on regulations. The City also developed an online marketplace where restaurants could buy everything they need to open a compliant streetery.

“The idea was to increase the design quality, but also make them safer and easier,” says Jacob Dugopolski, senior associate at WXY Studio, which worked on streetery designs with the city.

Singh’s is one of four streeteries designed in partnership with the city by WXY Studio. The modular, easy-to-assemble designs are posted in the marketplace so that anyone can recreate the setup. In addition to adhering to the City’s regulations, the designs have easy-to-replace parts and they’re all elevated for stormwater irrigation. The current setup was on display earlier this month as part of the NYCxDesign festival.

“The structure has been doing us a great job and it provides a really nice place [for people] to sit down and enjoy themselves,” Singh says.

Now that they have tested some designs and opened the marketplace, New York is getting ready to end its pilot program. Restaurants need to apply for four-year permits by August 3 and build or buy setups that comply with the new regulations. Right now, there are about 8,000 restaurants in the pilot program, according to the City’s Department of Transportation.

“I think a temporary program … allows for design flexibility. People do things quickly and test things out,” Dugopolski says. “We want this to be more worthwhile and easy for everyone in the city.”

Streamlining the application process

Some restaurant owners in Philly have already given up on their streeteries, choosing to disassemble their structures rather than wade through the bureaucracy of getting the proper license.

A modular program with a public-private marketplace a la NYC could help get more streeteries back in our streets. Rather than hiring architects and spending tens of thousands of dollars to design their own streeteries, restaurant owners could just purchase a kit that aligns with city regulations. Yin, who also owned the now closed restaurant High Street on Hudson in Manhattan, admires what New York City has done.

“I can’t imagine [the City is] making as much money off parking spots that you would be off of selling food and drinks. I think there’s way more money for the city of Philadelphia to be made by expanding our dining rooms.” — Good Dog’s Jeff Kile

“I see the modular program and I think that’s really cool,” she says. “If somebody has a standard built thing and if you want to use it, then it’s automatically approved.”

Another way Philadelphia could make the process of getting a streetery license easier is through reducing the number of City departments a restaurant has to work with to build a streetery.

In Pittsburgh, city officials changed a law that required restaurants to get approvals from three departments — Department of City Planning, Department of Permits, Licenses, and Inspections, and Department of Mobility and Infrastructure — for their streeteries. Now, the Department of Mobility and Infrastructure manages the program through a single permit.

“In some cases, the standards between departments were contradictory, and the convoluted permitting process was difficult for both applicants and staff,” says Katie Wettick, senior right of way manager with the City of Pittsburgh Department of Mobility & Infrastructure. “With the new regulations and better communication between departments, reviews are more streamlined.”

Bringing outdoor dining back to Philly

Councilmembers are already working to improve Philly’s broken streetery system — hopefully implementing enough changes ahead of this year’s peak outdoor dining season.

At the end of February, City Councilmember At-Large Rue Landau introduced a resolution calling for a comprehensive review of Philly’s outdoor dining regulations. The sister of Vedge owner Rich Landau, Landau is sympathetic to the struggles restaurant owners faced during the pandemic. One of her brother’s restaurants, the Rittenhouse-based V Street, had to close permanently in 2020. Landau wants to help restaurant owners who have already poured a lot of money into their streeteries to deal with less convoluted city regulations.

“The biggest complaint we’ve heard from the owners is that the process isn’t streamlined. It’s cumbersome. It’s confusing. There’s too many City departments to talk to and places to go,” Landau says. “Our goal is to help make this easier for them so that we can make this as quick and easy as possible and make it a win-win for all of us.”

Landau is speaking alongside Dugopolski and his WXY Studio colleague David Vega-Barachowtiz at a virtual event from 10 to 11:30am on June 4. The talk aims to consider the future of Philly’s outdoor dining program and how it can follow the lead of cities like New York.

Landau’s review of streetery regulations has already made things easier for restaurant owners. The adjacency issue Good Dog Bar has struggled with? Last week, City Council approved a bill that allows a streetery to extend beyond the boundaries of a restaurant with the written permission of the owner of the neighboring property.

“If they let us put it up in neighboring properties, we could put another three or four tables out there in front of the building,” Kile says. “I can’t imagine [the City is] making as much money off parking spots that you would be off of selling food and drinks. I think there’s way more money for the city of Philadelphia to be made by expanding our dining rooms.”

Correction: This post has been updated to reflect that High Street on Hudson in Manhattan is no longer in business.