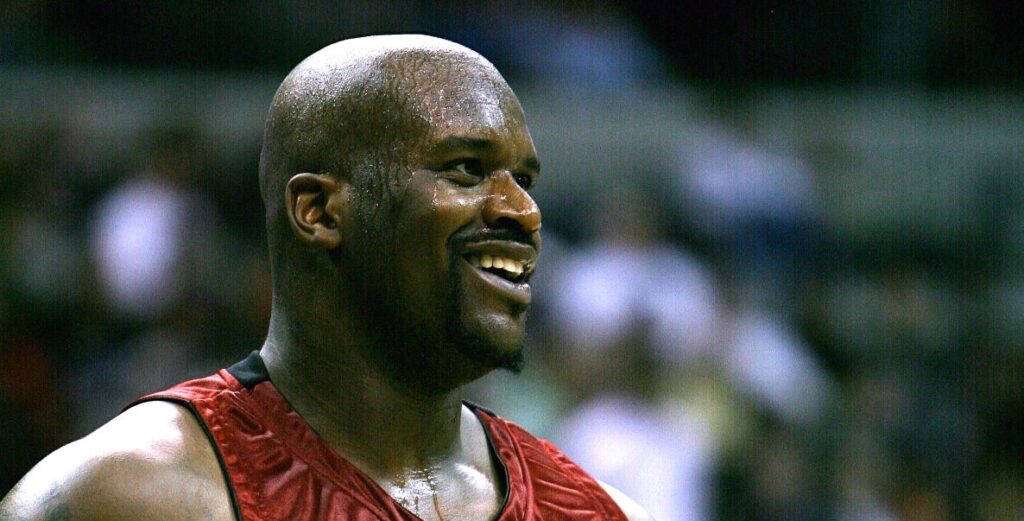

It was a beautiful, busy Arizona day in 1999. As the Executive Officer of the West Campus of Arizona State University (ASU West), I was checking an accumulation of voicemails when what to my wondering ears should I hear but the voice of someone identifying himself as … Shaquille O’Neal.

Shaq referenced a colleague, whom I knew well, who had told him that I could help him fulfill a promise to his mother to complete his bachelor’s degree. I checked with the colleague; it wasn’t a hoax. Shaq was not getting the help he needed from his former school, Louisiana State University (LSU), and asked if ASU West would review his credits and arrange for him to take the two courses he needed to graduate.

Absolutely! We connected Shaq with advisors who arranged for him to take degree-completing courses according to his own schedule and convenience, even then using online options. When LSU found out that Shaq was putting together a plan with ASU, they quickly changed their tune and found a way to assist their former basketball star and then Los Angeles Lakers champion.

Smart move, LSU! Why would you want to share Shaq’s fame and philanthropy with another university? It’s amazing that LSU at first even hesitated. That shows that less famous drop-outs would encounter potentially insurmountable difficulties in getting their degrees.

Millions are like Shaq

Forty million students, few as famous as Shaquille O’Neal, have attended American colleges but never graduated. Without Shaq’s confidence to pick up the phone and call their home university, or any university, millions of students are left in limbo, often with heavy burdens of student debt.

It is essential that every Philadelphia-area college and university develop programs to prevent students from dropping out in the first place.

That’s why Delaware State University (DSU), a Historically Black University in Dover, has teamed up with the Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF), the nation’s largest organization exclusively representing the Black College Community, to help students complete their college education. The Joint Center for HBCU Non-Traditional Completion will build on $500,500 in grants from the Kresge Foundation and Ascendium Education Group that supported a three-year pilot program targeting people with 90 or more college credits who never finished.

So far, the program has helped 60 DSU students graduate, with hundreds more in the pipeline. For the pilot, DSU recruited students who had left the university before receiving their degree, offering them eight-week courses online or in-person to help expedite their learning. The Joint Center is now a resource for other HBCUs looking to help their almost-grads get their degrees.

Debt…but no degree

As I have written before, students drop out for any number of preventable reasons. According to an IHEP (Institute for Higher Education Policy) study last year, 14 percent of almost-alumni had financial holds on their accounts, or had failed to pay a library fine, and about 62 percent had neglected to fill out a graduation application — technicalities that had nothing to do with whether or not they completed their coursework.

This was often one last obstacle too much. Throughout their time on campus, first-generation college students often feel like strangers in a strange land. Higher education bureaucracies and personal problems set daily hurdles. Nonetheless, students will deal for years with food and housing insecurities and other fundamental challenges to completing the requirements for a degree. And yet, they leave campus without one.

The IHEP report also found that about 33 percent of all students studied, and more than 50 percent at four-year institutions, lacked just one major-required course. These students, too, left college without the credential they had almost earned.

That has consequences beyond a diploma: Studies show that people with bachelors degrees earn 84 percent more than those with only high school degrees, and are half as likely to be unemployed. College grads also have a 3.5 times lower poverty rate. For people who started college but never finished, lower salaries are often combined with student loan debt, a burden that sometimes has no escape.

DSU’s efforts are changing that trajectory. “The [almost grads] came to the university and have finished their bachelor’s degree with Delaware State and have now improved their social mobility and are gainfully employed,” Terry Jeffries, assistant dean for the School of Graduate, Adult, and Extended Studies at DSU, told The Philadelphia Tribune.

The best way to help college students like Shaq

It is essential that every Philadelphia-area college and university develop programs to prevent students from dropping out in the first place. How to do that? They could set up senior-year scholarships to cover small debts for students in good standing and on track to graduate. Most important, they could make sure that every student has a caring person to go to for guidance — an advisor, a faculty member, a peer mentor. If colleges and universities have identified these guides, it becomes somewhat easier to track down drop-outs and help them return. It’s also clear in the TMCF/DSU pilot, and in Shaq’s case, that offering quality online instruction can remove hurdles to finishing those last few courses.

LSU (finally!) let Shaq fulfill his promise to his mother. He graduated in 2000, with a degree in general studies and a minor in political science. (He then went on to get his Doctorate in Education from Barry University.) Coach Phil Jackson let O’Neal miss a home game so he could attend graduation.

But what about the 40 million unfulfilled promises to mothers? Let’s make it so that you don’t have to be famous to complete a college degree.

What We Can Do:

-

- Find out what your alma mater is doing to reach out to students who have dropped out.

- If possible, provide universities with philanthropic support for outreach efforts.

- Encourage students you know to find ways to complete their degrees.

Elaine Maimon, Ph.D., is an Advisor at the American Council on Education. She is the author of Leading Academic Change: Vision, Strategy, Transformation. Her long career in higher education has encompassed top executive positions at public universities as well as distinction as a scholar in rhetoric/composition. Her co-authored book, Writing In The Arts and Sciences, has been designated as a landmark text. She is a Distinguished Fellow of the Association for Writing Across the Curriculum. Follow @epmaimon on Twitter.