[Ed note: The Citizen is hosting its inaugural Ideas We Should Steal Festival on November 30th, at Drexel University’s Mandell Theater. Join us and Hear Cat Goughnour share more about community and what it could mean for Philly. See here for tickets and info.]

Cat Goughnour returned home to Portland, Oregon from London with a master’s degree in Sociology from the London School of Economics under her belt, excited to pursue a job in the field and move in with her brother, who owned a home in North Portland. Instead, she spent a year living with her mom in a friend’s garage because her brother’s house was foreclosed on, partially as a result of rising property costs.

Goughnour had been displaced, she and her family collateral damage of a neighborhood they could no longer afford, a common occurrence in Portland, considered the most gentrified city in America. “We were essentially homeless, definitely houseless,” she says. “I came back thinking I could build a life now that I was newly educated. Instead I spent a year unemployed and trying to understand what had happened.”

Goughnour joined a few regional housing advisory councils, and quickly noticed that even when city residents sat on these councils, they often weren’t the people—poor and African American—who would likely be negatively-impacted by new city developments. “Many of the community members who are most impacted by these issues are not at the table,” she explains. “And the needs of the people are often very different than what other people are saying the needs of the people are.”

“I find it a moral imperative,”Goughnour says. “We have already lost so many generations to policy poorly-implemented. My purpose is to use whatever opportunities I’ve been given or made to see that doesn’t happen anymore.”

Like most cities, including Philadelphia, Portland at the time required developers to engage community members only after a plan is in motion—giving them a chance to weigh in on the implications of development, but not to help shape it from the start. Goughnour thought it didn’t have to be that way. She founded Radix Consulting Group, a certified B Corp, to develop a process for community-inspired and community-led urban development that would benefit everyone.

A few years in, her work has helped to instill changes in Portland’s development plan; she is now talking to Detroit and Minneapolis about spreading her work to those cities, as well.

![]()

Along with an anti-displacement group, ADPDX, Radix developed 11 community-focused principles of land use, including shifting some funds to help keep people in their homes; emphasizing “permanently affordable” models of home ownership; instituting renter protections; and deliberately including lower-income community members of color in the development planning process.

“What we’ve found is there is an understanding that gentrification is happening but there isn’t a focus on people,” she says. “There’s a lot of focus on place. It’s not looked at as a public health issue, which it is.”

A version of those principles were included in Portland’s 2035 Comprehensive Plan, published in December of 2016, which states: “The City of Portland seeks social justice by expanding choice and opportunity for all community members, recognizing a special responsibility to identify and engage, as genuine partners, under-served and under-represented communities in planning, investment, implementation, and enforcement processes, particularly those with potential to be adversely affected by the results of decisions.”

Unlike in Portland, Philadelphia is at a point when gentrification can still be managed. Most Philly neighborhoods—even those around Center City—are not experiencing the financial upheaval that signals gentrification. But the ones that are—like Graduate Hospital—are significant reminders of what can happen to a community.

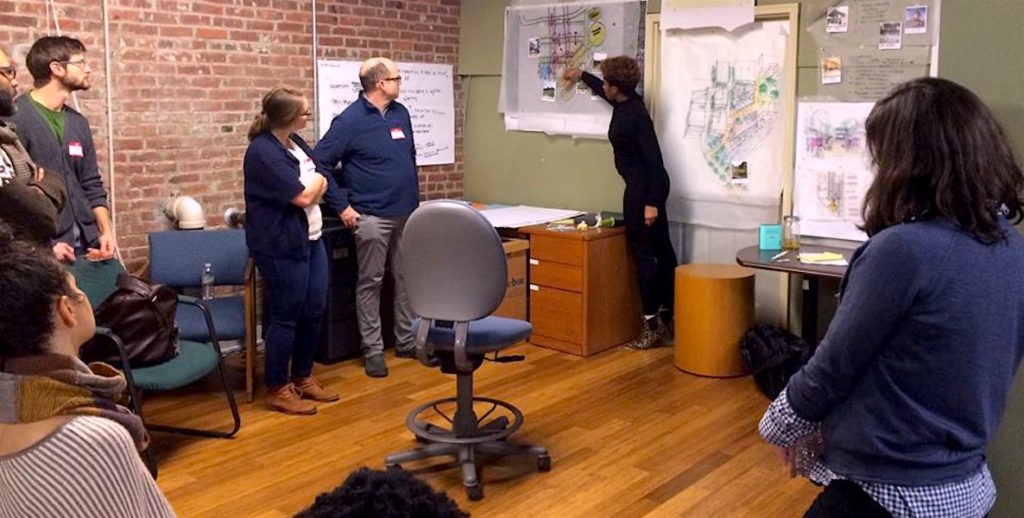

The comprehensive plan only went into effect this past May, but Goughnour spent the intervening months demonstrating how it could work in real life. With the help of the Center for Public Interest Design, Radix hosted a workshop that brought together community representatives with more than 30 architects and urban designers to look at underutilized parcels of land in the city and how they could be used to benefit both community members and developers.

In particular, they took on the Albina District, the historic heart of Portland’s African American community, and the centerpiece of a book about gentrification, What a City is for: Remaking the Policies of Displacement by Vancouver writer Matt Hern. Together, the group created a master plan for the area that included a pedestrian corridor to connect neighborhoods, with an entertainment venue, a community resource center, and a food market, as well as increased building of small housing as an affordable option for residents who might otherwise be pushed out.

The development plan, Right to Root, has not yet been adopted, but Goughnour is talking to the city and others about how to implement some of its ideas.

“The goal is to really show that for a very nominal amount of money or a land transfer of underutilized land, we could build a hub for everything else to happen,” explains Goughnour. “What would be the ultimate win would be having a dedicated space where we’re able to have a market and a place to start gathering and building together. I think it’s possible.”

Unlike in Portland, Philadelphia is at a point when gentrification can still be managed. As a Pew Report noted last year, most Philly neighborhoods—even those around Center City—are not experiencing the financial upheaval that signals gentrification. But the ones that are—like Graduate Hospital—are significant reminders of what can happen to a community: The percent of mostly working class African American residents of the South Philly neighborhood dropped from 90 percent to 38 percent from 2000 to 2014.

Elsewhere, housings costs are rising while incomes are stagnant or lowering, as in parts of North Philly, where the median home value tripled between 2000 and 2012, and the median income decreased by 6 percent. The black population in North Philly decreased by 22 percent in this same time period. In other parts of South Philadelphia, where the median home value increased by 184 percent, the black population dropped by 29 percent.

Ensuring collaboration would mean a shift in how planning happens in Philadelphia. Landis says the best way would be for the city to hire urban design consultants to work with RCOs to bring the ideas of community members to fruition, something Vancouver, British Columbia, has dabbled with.

Right now, says John Landis, a professor of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia’s approach to property development is actually pretty progressive. If a developer wants to embark on a project that isn’t up to code—and the vast majority of them are not—he must apply for a variance. To get that variance from the Zoning Board, he must obtain a letter from the neighborhood’s Registered Community Organization, or RCO. The RCO engages with the community, provides feedback, and either supports the project or doesn’t.

This process, though, doesn’t guarantee that the community’s voice is reflected in the final project. This depends on both the quality of the RCO—they are not all created equal—and how heavily the zoning board takes the RCO’s opinion into consideration, as projects can be approved without the RCO’s support.

And of course, projects like the Temple football stadium come to mind. The project is roiling residents’ tempers; though no residents would be displaced, neighbors fear rowdy crowds, and higher rents and complain that besides students, the university has not engaged the community in its planning. The university is creating a plan to address community concerns—community gardens to disguise the barriers of the stadium, amenities available to residents all year long, on-campus tailgates to keep drunken fans to a minimum, a study of increased traffic to identify solutions—the overarching takeaway has been a distinct lack of collaboration.

“It didn’t have to be that way,” says Landis. “If all sides had stepped back and said, ‘Wow, this is a great opportunity to get some improvements for everyone,’ it might have worked.”

Ensuring that collaboration would mean a shift in how planning happens in Philadelphia. Landis says the best way would be for the city to hire urban design consultants to work with RCOs to bring the ideas of community members to fruition, something Vancouver, British Columbia, has dabbled with. Otherwise, the work is simply “an exercise in community aspiration.”

“The community-based model doesn’t really deal with the fact that the city or the developer has control of the land and process, and community members don’t have much power other than to say no,” he says. “It produces proposals that the developer won’t be interested in or the city won’t help fund.”

In Portland, Goughnour acknowledges that it will take more than just changing the planning process to ensure people can stay in their homes. She has also begun tackling the problem in other ways, by helping to create economic opportunity for black residents in the neighborhoods where they live. She set up community markets for two neighborhoods to allow black small business owners to build financial capital, and she started a collective that supports black women in Portland starting or scaling up small businesses; eight of 10 members registered their businesses with the city last year.

It is, in aggregate, about changing the way we think about communities—who is in them, who shapes them, who gets to decide what happens to neighborhoods as they change and grow and (hopefully) become better places to live.

“That will only happen if we are very intentional about how we set up these processes for the future,” Goughnour says. “I find it a moral imperative. We have already lost so many generations to policy poorly-implemented. My purpose is to use whatever opportunities I’ve been given or made to see that doesn’t happen anymore.”