The 2019 property assessments came out last week, and we can already tell that the Office of Property Assessments botched it once again.

The assessment issues are complicated, with a lot of different moving parts to keep track of like market values, sale prices, tax rates, and separate assessments for land and improvements (buildings plus property renovations.)

Land assessments are especially important to get right, because the city overall has seen its land values greatly increase over the last several years, and our local tax system has been poorly set up to take advantage of this increase in land wealth to fund city services. A recent report from University of Michigan and University of Illinois economists estimated Philadelphia’s total land value at approximately $400 billion.

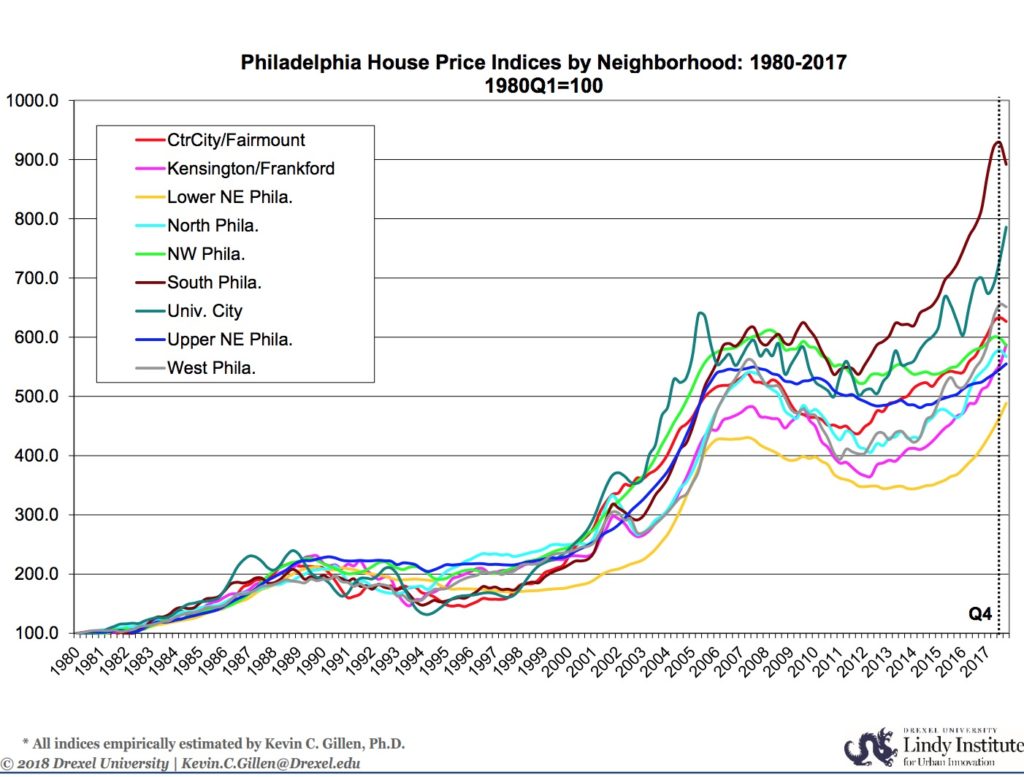

Anyone who’s been following Kevin Gillen’s quarterly real estate reports for the Lindy Institute knows Philly’s real estate market has been seeing steady price growth in all regions of the city, especially over the last couple years, and a key question about this is the extent to which it’s being driven by higher-priced fancy buildings, versus people just bidding up the prices of the existing older housing stock.

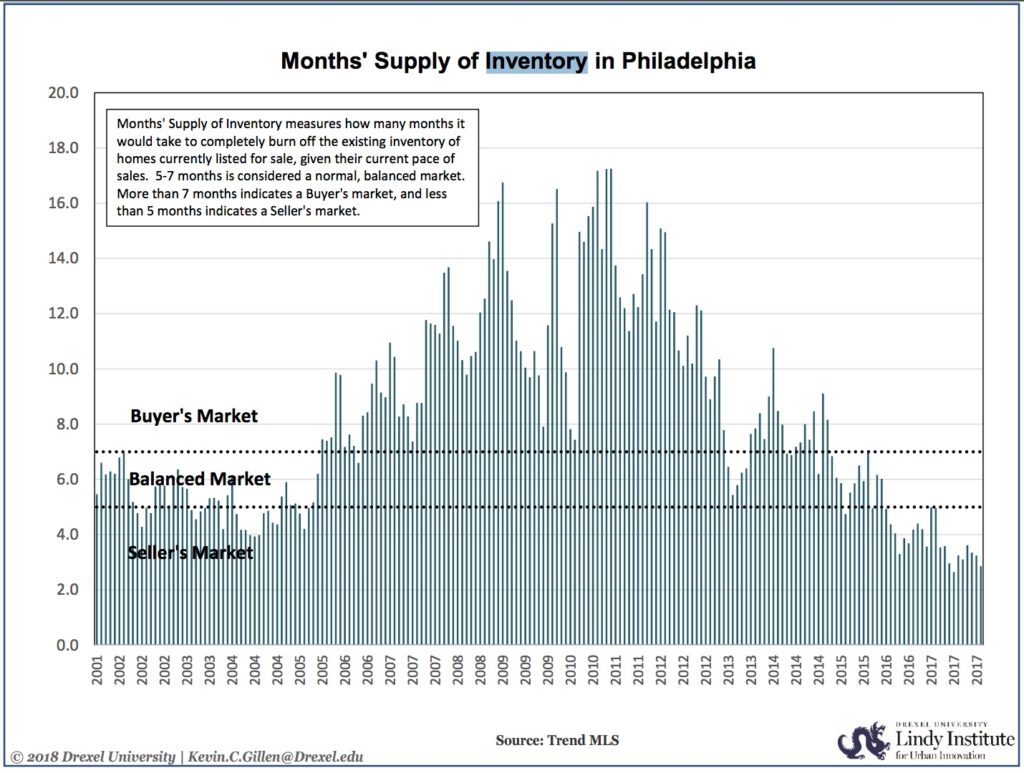

While we’ve certainly been building a lot of new housing relative to our own recent past (though a pretty mild amount by historical standards), we haven’t been building enough housing to get back into Buyer’s Market territory.

That shortage of inventory has sent prices higher, with the same old houses going for more money as some neighborhoods become more in-demand, and this inflationary trend is responsible for some portion of the increase in prices.

This is land value. It’s derived from the rising value of certain broader locations, often closely tied to school catchments. It’s different from improvements—owners investing money in improving the quality and value of their properties. The more parents who want to live in the Meredith catchment in Queen Village, for example, the more homes in Queen Village will see their values increase—even older homes that haven’t been renovated in years.

In Graduate Hospital, where all the rowhouse lots are nearly identical in size, land value bounces around significantly per property, from $65,000 in one case to over $250,000 in another! It looks like they’re just taking 30 percent of the total assessed value and ascribing it to land.

When the city assesses land value, it doesn’t take into account these location factors. If they did, land assessments on the same block would be roughly the same on a square footage basis. Instead, the Office of Property Assessment backs land value out of the improvement value, leading to the absurd situation where we see big swings in land values within the same block.

Here is a breakdown of the 2000 block of Pemberton in Graduate Hospital, where all the rowhouse lots are nearly identical in size. You can see that land value makes up almost exactly 30 percent of assessed value for all properties on the block, and bounces around significantly per property, from $65,000 in one case to over $250,000 in another! It looks like they’re just taking 30 percent of the total assessed value and ascribing it to land.

Why should we care about this? If we’re systematically undervaluing land—particularly unimproved land in the heart of the central business district—then we’re leaving a ton of tax money on the table from particularly wealthy sources, and we’re also over-taxing everyone else as a result.

OPA’s reasoning for this is that they think new buildings add more value to land, which is true to an extent, but the effects wouldn’t stop at the property line—they’d impact the whole block’s land values. To get the land assessments more right, you’d really want to start with a square footage-based assessment of land values so that they’re relatively uniform within blocks and neighborhoods, and then back the building and improvement values out of that.

We need to get the new CAMA (Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal) system up and running to do something like that, but because the City can’t seem to manage any IT projects, it keeps falling behind. Here are the last three years of statements from the administration’s Five-Year Plan. Note the increasingly slippery language around the delivery date:

Five year plan, presented 2016:

“Working with the Office of Property Data (OPD), OPA took the next steps toward acquiring a Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA) system by issuing an RFP and selecting a vendor. OPA expects the project implementation stage to begin in FY17 and to be completed by FY19.”

Five year plan, presented 2017:

“Data cleansing efforts and pre-work for the CAMA project have already begun, and full implementation will kick off in late 2017 or early 2018. Please see the Office of Property Assessment chapter for more details on the City’s plan for regular assessments going forward.”

Five year plan, presented 2018:

“The Kenney Administration is committed to that goal, and is investing in state-of-the-art technology through a CAMA (Computer-Assisted Mass Appraisal) system that will provide an automated and efficient methodology for valuing properties. The CAMA system is expected to be in place in FY20.”

Why should we care about this? Simply put, land values spike in Center City and fan out from there, and if we’re systematically undervaluing land—particularly unimproved land in the heart of the central business district—then we’re leaving a ton of tax money on the table from particularly wealthy sources, and we’re also over-taxing everyone else as a result. And on the land use side, by undertaxing vacant land in appreciating areas, we’re effectively subsidizing land speculation that’s not in the public interest.

We’ll be interested to see the broad trends as the media begin digging in further, but already it’s clear the land values fail the uniformity test and should be challenged.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog