The fourth grader quivered at the defense table as his three accusers described his crime—stealing chickens from their farm. His wife on the witness stand broke down in tears, pleading with the jury to understand: Her husband was a hero, trying to keep his family from starvation. His lawyer, in turn, accused the chicken farmers of gross violence for shooting off the thief’s tail. Was Mr. Fox justified? Should he go to jail?

In the front of the room at Edwin M. Stanton Elementary School, Appellate Court Judge Midge Rendell sent the jury of fourth grade peers out of the room to deliberate. They returned a few minutes later with their verdict: The crime was justifiable. But, they wondered, could they convict the farmers for shooting Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox?

“It was amazing,” says Rendell. “The kids reasoned through the moral of the story, and came to a conclusion. They were incredibly proud of themselves.”

Rendell presided over the fourth grade mock trial as a pilot project of her Rendell Center for Civics and Civic Engagement, a two-year-old nonprofit that aims to revive civics learning in Philadelphia schools and beyond. At Stanton, Rendell and her fellow judges presided over trials in every grade, using books they read in class, to understand from the inside the way American law works for—and is created by—citizens. It was just one piece toward the larger goal of increasing citizenship, starting with our youngest citizens.

In the 70s, kids even learned civics by watching Schoolhouse Rock! on Saturday morning TV.

“We want a more engaged citizenry,” Rendell says. “We’ve ceded the power of the people to the few. We’re doing exactly what the Founding Fathers didn’t want. People don’t vote; they tune out what they think is government, but is really a lot of things that are relevant to their lives.”

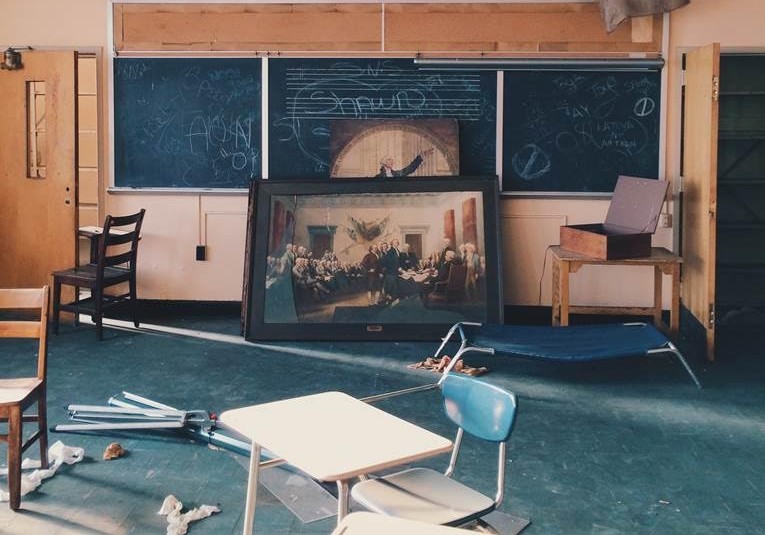

How dire is it? Less than one-third of eighth graders understand the purpose of the Declaration of Independence and between 1973 and 1994, the number of people who attended school board or town meetings, worked for a political committee or party, or served as an officer of a community group declined by over 35 percent.

Rendell is smack in the middle of a national movement to bring civics learning back in to the classroom, with the aim of creating adults who understand in a meaningful way the rights and responsibilities of being American. The goal of the movement is three-fold: To increase knowledge about our system of government; to teach the skills needed to write to a Mayor, or advocate for a viewpoint; and to encourage a civic disposition, so citizens feel empowered to make a difference in their communities. Years of academic research have shown that a strong classroom education in civics is linked to higher rates of voting, of volunteerism, of participating in public discourse—and, to come full circle, to lower dropout rates and better academic skills.

The movement dates back to 2003, to a groundbreaking report by the Carnegie Corporation and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Education (CIRCLE) at Tufts University that laid out the consequences of the last several decades, in which focused civics instruction has almost disappeared from the classroom. Up until the 1960s, students got separate courses in government, democracy and civics. Now, they often get only one semester on the workings of government—late in high school when it’s too late to reach many students. Partly, this is because there’s no time. With No Child Left Behind, all efforts turned to preparing students for standardized tests, mostly in math and reading. Without a test for civics, the message to educators was clear: If it isn’t tested, the saying goes, then it isn’t taught.

Not coincidentally, Americans today know about and do far less for their democracy than ever before. It’s not just voting participation, which even at its recent peak—the 2008 presidential election—saw only 57 percent of registered Americans casting a ballot. A recent national civics assessment found that less than one-third of eighth graders understood the purpose of the Declaration of Independence, and less than a fifth of high school seniors understood how democracy benefits from citizen participation. Minorities and poor students are less likely to attend schools with high-quality civics education, and far less likely to vote. And between 1973 and 1994, the number of people who attended school board or town meetings, worked for a political committee or party, or served as an officer of a community group declined by over 35 percent.

“Time has been squeezed out of the school day for non-STEM subjects,” says Ted McConnell, executive director of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, an advocacy group. “But shouldn’t we be concerned about what kind of citizen will be doing the math that leads to the technological breakthroughs to keep us advanced? Very few people will be doing that. Everybody will be a citizen.”

Rendell first enmeshed herself in the issue of civics education when she was Pennsylvania’s First Lady though PennCORD, a coalition that included the state Bar Association and the National Constitution Center. “It came to me that citizens have far too little appreciation of our form of government, and how it creates a good economy and other things that people from other countries flock to the United States to enjoy,” Rendell says. Like Rendell, the most prominent national advocate for civics education is also a judge—former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. “Judges see the value of our system in ways that others don’t,” Rendell says. “We see the laws work, which makes us unique.”

With No Child Left Behind, all efforts turned to preparing students for standardized tests, mostly in math and reading. Without a test for civics, the message to educators was clear: If it isn’t tested, the saying goes, then it isn’t taught. Now Pennsylvania will be one of five states to mandate a civics assessment before graduation; the Keystone Exam in Civics will debut in 2020.

Although she was barred from lobbying, PennCORD’s work influenced lawmakers and led to Pennsylvania’s mandating a Keystone Exam in Civics that will debut in 2020. Five states require students to pass the immigration naturalization exam for new citizens; another dozen have similar proposals in the works. They require little more than than a regurgitation of easily-forgotten facts. (Kind of like this.) McConnell says he expects—or maybe hopes—that the Pennsylvania test, which is still being developed, will expect some higher-level thinking from students. (He also refers to Rendell as a “national hero among civic educators.”) To Rendell, though, the content of the test matters less than the fact of it. “I’m concerned about there being a test so teachers know they have to do something in these areas that otherwise would not be taught,” she says.

Still, testing alone is not the answer to developing informed and engaged citizens. Rendell’s work with elementary school kids hearkens to what educators have noted for years: It’s important to reach students early, and to engage them in lessons beyond a textbook. In a report co-edited by Penn’s Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools makes several recommendations for comprehensive civic ed, from classroom studies to community service to student government. The state that most aligns with this idea is Tennessee, which could teach Pennsylvania—or at least Philly—a few things about civic education. Starting this past school year, Tennessee students were required to complete one project-based civic assessment in middle school, and one in high school. The legislation is broad in its language, but the intent is clear: Students are being asked to engage in a civic issue and understand how to affect change through government and advocacy.

In Philadelphia, we’ve taken small steps in this direction. Constitution High School, a magnet school in partnership with the National Constitution Center, has a curriculum tied to civic engagement; it even has its own student constitution developed by the its first students, the class of 2010. Need In Deed, a nonprofit teacher network, promotes service learning and civic engagement in individual classes around the district. Even the city’s African American studies requirement, implemented in 2009, is part of this effort. If done well, the course provides an in-depth look at the role of individual interests in government; at how laws are made; at how individuals, groups and movements can affect change; at controversial current events that teach students how to engage each other and the world. And that, ultimately, is what will make them into engaged adults working to affect the change they want to see.

“All this allows students to experiment with small d-democratic processes,” McConnell says. “Kids come to the realization that it was the average people who put their lives on the line, the forgotten person who joined together to make the change. These things help kids come to the realization that they can make a difference. That’s the goal.”