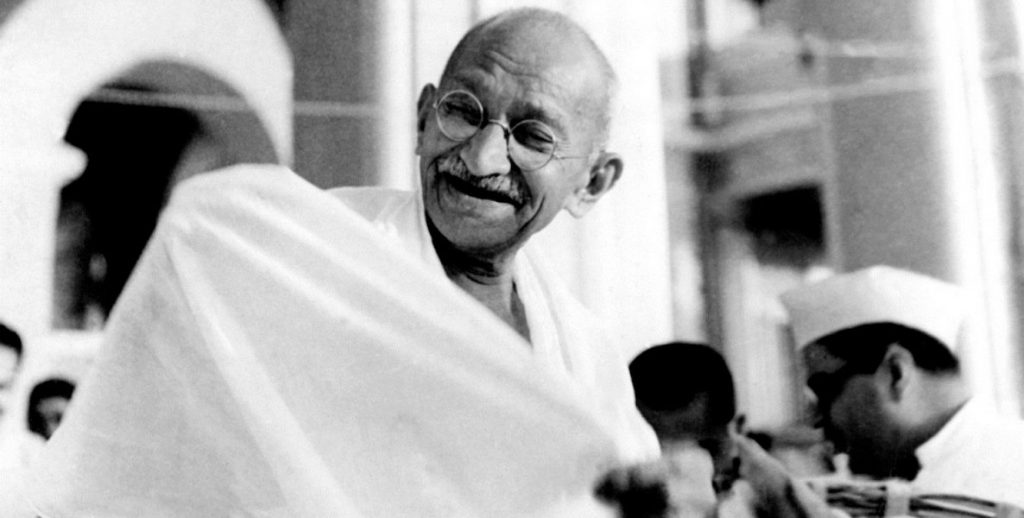

What could Mahatma Gandhi have been thinking when, on the eve of World War II, he typed a brief plea to Adolf Hitler, importuning his “friend” not to set Europe ablaze? Did he really believe a seven-line letter, barely sufficient to fill a postcard, would provoke a change of heart in a man plotting the violent domination of an entire continent? Did he think the tone of his missive, deferential to the point of obsequiousness, would appeal successfully to the Fuhrer’s titanic ego? Perhaps Gandhi, already lionized by millions of his countrymen, was so convinced of the force of his own charisma that he presumed he could change the course of history with a quick note, dashed off in the bunting of a dubious humility. Maybe, to take the cynic’s view, the correspondence was an act of cynicism itself; a perfunctory, un-spellchecked intonation of protest to be registered and ticked on a to-do list.

Of course, just as Gandhi could not have known on July 23, 1939 the magnitude of the horror Hitler would unleash over the next half-decade, neither can we be certain of the nature of Gandhi’s intentions and expectations in sending that letter. All we have is history. And as history had it, the letter never reached its recipient, having been intercepted by the British government, a common foe—it bears mentioning—of Hitler and Gandhi both. Few are so naïve as to speculate that it would have made a whit of difference if Hitler had actually received the note, his diabolical ambitions being what they were. Just as likely, Hitler would not have been moved by sympathy for the persona and political stature of its writer. In a 1938 meeting with Lord Halifax, Hitler had proposed that the British Empire curtail the agitations of the Indian National Congress in a straightforward manner, by assassinating Gandhi. Whatever counterfactual scenarios we may now entertain within the spacious comfort of nearly 80 years’ hindsight, the pertinent reality is this: mere weeks after Gandhi posted his letter, Hitler’s forces invaded Poland and, as Gandhi had put so concisely, “reduced humanity to the savage state.”

The nominee of one of the two major political parties conducted a presidential campaign whose messaging consisted primarily of outlandish, impulsive tweets and the amplification of toxic slurs from fringe nationalists. The other side’s standard bearer squandered an inordinate amount of energy grappling in the gutter with her opponent, or pandering to unconvinced constituencies with vapid memes and slogans of her own.

So what are we now to make of this humble artifact of failure, now that both its author and its intended reader are long dead, their memories respectively exalted and deplored, each reduced to broad stroke metonyms for good and evil? Is it nothing but a curiosity? The answer to a trivia question? A point of departure for a flight of fancy on an almost-interaction between a dichotomous pair of historical caricatures? The artist Jitish Kallat posits that Gandhi’s letter has much more to tell us about ourselves and our civilization than its few meek sentences denote. In his 2012 installation Covering Letter, Kallat exhumes the correspondence from its historiographical crypt and transubstantiates it into something at once dreamlike and tactile, lambent and shadowy, enveloping and ephemeral. Encountering Covering Letter, one enters a darkened corridor illuminated only by the projected image of Gandhi’s letter scrolling along the floor and up the length of a screen at the far end of the installation. Upon approach, the screen reveals itself to be a curtain of fine mist, diffusing at its base as the projected text crawls upward in an apparition of urgency. To exit the installation, a visitor, with her elongated shadow in tow, must walk through the mist, through Gandhi’s words, and into whatever awaits on the other side.

In the reconceptualization of Gandhi’s entreaty into a phenomenon that encloses and quite literally touches those who experience Covering Letter, Kallat seeks both to personalize and universalize the communique, transforming it into a message that could have been written “to anyone, anytime, anywhere.” Indeed, untethered from its historical moment and the two individuals responsible for its genesis, the subject of Covering Letter offers a profound commentary on the here and now. With its performatively reticent tone, its concise and formal structure, and even the fact of its having been typewritten, in ink, on paper, Gandhi’s letter to Hitler is self-evidently an object of a bygone era. Yet there is an irony in this. In our new century, textual communication is more prevalent than ever. This is the epoch of Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr and those cesspools of internet discourse known as comments sections, where everyone can declare themselves Men of Letters and nearly everyone does. It has never been easier to find a megaphone with which to broadcast one’s “humble opinion.” The only challenge, in this new age, is being heard above the din.

But it is this very din, this cacophony which passes for communication today, that tends to render Gandhi’s letter, as such, antiquated and foreign. With our newfound technological ability to expound pseudonymously across fiber optic cables, we may fearlessly launch trebuchets from behind the fortresses of our IP addresses and screen-names. Likewise, we can deny that the targets of our slings and arrows have faces, eyes and hearts whose expressions of injury might cause us remorse were we actually to behold them. Consequently, our use of words no longer serves to offer or seek elucidation, consolation, or reconciliation. Instead, our words, divorced from meaningful ideas, are reduced to signifiers. In the Internet era, our words have become weapons, embraced, fetishized and exploited without being fully understood, much like the military technology that wrought such carnage in the World Wars. But our words today function also as the code words, battle cries and war paint of the innumerable factions waging online rhetorical battle with each other and within themselves, at all times, everywhere, about everything.

And to engage in the world today is to be a partisan in those battles. It is a basic function of social media (and all media have become social) to create balkanized communities. We have each found our tribe, and if we have not, one surely has found us. For every preference, predilection, philosophy and prejudice, there is a Facebook page, a Reddit category or a collection of Twitter followers waiting to welcome and reinforce our biases. If Gandhi’s letter to Hitler was inhaled by a vacuum of power, then our all-caps, curse-filled rants ricochet around our echo chambers of crowd-sourced rage, gaining speed as they jettison restraint. Our tribes then become ghettos of grievance, spoiling ever for a fight and finding purpose nowhere but in confrontation with the Other. Woe to the virtuous idea, for inevitably it will dissolve in bile.

Gandhi’s words and his life remind us that we are responsible for bending the moral arc of the universe toward justice, treading its path beyond the horizon and toward whatever awaits on the other side.

One might counter that the kind of coarse rancor that so dominates the online universe is the domain of crackpots, basement-dwelling malcontents, and a mass of society that has too much free time or too little free time to do anything productive with it. The elites, the thinkers, our leaders, one might assert, are above such vulgarity. Surely those with their hands on the levers of power grasp, if not the art, then at least the value of conscientious communication. We need look no further than the 2016 presidential election to see that reality tells us otherwise. The nominee of one of the two major political parties conducted a campaign whose messaging consisted primarily of outlandish, impulsive tweets and the amplification of toxic slurs from fringe nationalists. The other side’s standard bearer attempted to stay above the fray, but squandered an inordinate amount of energy grappling in the gutter with her opponent, or pandering to unconvinced constituencies with vapid memes and slogans of her own.

Is there any hope? Gandhi’s example gives us reason to believe there is. As the adage goes, the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Though Gandhi’s letter to Hitler failed abjectly in achieving its stated purpose, the dictator’s ultimate aim of establishing a thousand-year German empire came to naught while Gandhi’s dream of an independent India was realized, in both cases at a tremendous, calamitous human cost. Was that justice? The moral universe’s arc is perhaps far too long for us ever to know. Still, as we consider Gandhi’s words— both in their original context and as the subject of Covering Letter—against today’s descent toward the written word’s lowest common denominator, suspicions of a cynical motive on Gandhi’s part fall by the wayside. For all of its epistolary modesty, the letter is if nothing else, premised upon the humanity of its recipient. Gandhi insistently, stubbornly refused to regard Hitler as something other than or less than human. With our hindsight, it is easy to regard that insistence as frustratingly futile. But in this modern era in which the first move in any war of words is to dehumanize our opponents, we can appreciate a moral nobility in Gandhi’s insistence on recognizing the humanity in even the worst of humankind, despite its futility. Gandhi’s words and his life remind us that we are responsible for bending the moral arc of the universe toward justice, treading its path beyond the horizon and toward whatever awaits on the other side.

Ajay Raju, a co-founder of The Citizen, is an attorney and philanthropist whose Pamela and Ajay Raju Foundation purchased Covering Letter for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This column is his response to the prompts in the essay contest the Raju Foundation, The Citizen and 6ABC are launching this week for area high schoolers.