There are many things we could never have predicted before November 8th (including, of course, the results on November 8th). But one of the strangest, least expected outcomes of Donald Trump’s election has taken root here in Philadelphia, and throughout the state: Suddenly, the subject of gerrymandering has become very sexy.

Gerrymandering is what happens when legislative redistricting breaks bad. Every 10 years, after the Census comes out, states have to redraw their congressional and state legislative district maps to account for population changes. In theory, this should be a straightforward, politically-neutral process. In reality, the lines are often drawn in ways that can only be described as contorted and tortured in order to benefit the party who controls the process.

Actually, it’s the opposite of gerrymandering that has suddenly become a popular notion—that is, the reasonable redistricting of political boundaries in the state of Pennsylvania, to ensure better and more equitable elections. It’s a thankless task; one not popular with many politicians; and one that promises a long, slow slog to success. “People don’t just wake up one morning and say, ‘Ah, redistricting, that’s my thing,’” says Fair Districts PA Chair Carol Kuniholm. But, clearly, more and more people are making redistricting their thing.

Fair Districts PA, an offshoot of the League of Women Voters, is dedicated to redistricting reform in Pennsylvania. They’re trying to build support and recruit volunteers for this task of fixing the way we draw lines. Last month, they held an event at the Arch Street Presbyterian Church, hoping to attract 200 people or so to hear Kuniholm give a presentation about the issue. Even they were a bit surprised when over 700 people came out, nearly bursting the church’s capacity. Meanwhile, they’re adding about 1,000 followers a week on Facebook, topping 9,700 followers as this story was written. They have county-based groups across the state, and have several local groups within Philadelphia itself.

The Fair Districts plan is based on other commissions that are already in effect—and effective. Canada, Great Britain, and even Arizona all have nonpartisan redistricting commissions that draw fairer boundaries.

Everyone involved in Fair Districts has their own story of how gerrymandering came to be their number one issue. For Kuniholm, a former youth minister, it started when she couldn’t figure out why a new public school in Kensington wouldn’t have a library. The more she looked into it, the farther she went down the political rabbit hole. “I found that change can’t happen because the legislature is so broken,” she says. “Even representatives with the best intentions routinely run into shutdown from both sides. So I researched why it’s impossible to get good reforms through, and everything I read led me back to redistricting reform.”

Gerrymandering isn’t unique to Pennsylvania. It’s a problem all across America. So much so that in his final State of the Union address last year, Pres. Obama pointed to gerrymandering as one of the factors that hinders public trust in government.

Redistricting is, unfortunately, foundational to the way politics operates. It allows the majority party to redistrict their opponents out of seats, further increasing majorities that they often shouldn’t even have. It also creates uncompetitive districts, meaning that primary elections (whose outcomes are often decided by party bigwigs) control the ultimate outcome. But it even gets personal: Individual members can be redistricted out of their own seats, into hostile districts, or up against more popular incumbents. Party leadership pulls the strings in redistricting, using it as a hammer against legislators who dare exercise independence. “It’s the keystone of cronyism and control,” says Kuniholm.

Legislative redistricting in Pennsylvania is currently done by a five person committee. Two members are chosen by Republicans, two by Democrats, and the fifth by agreement of both parties. If the parties can’t agree—and when do they ever?—the fifth member is chosen by the state Supreme Court, which, as of last year, is controlled by Democrats. By law, they can draw the lines any way they please, as long as they meet the very few and very lenient constitutional restrictions on basic fairness.

The next redistricting in Pennsylvania will occur in 2021, after the results of the Census are sent to the states. But the folks at Fair District know that will be here before you know it. Especially since, under our state constitution, changing the way we draw lines will take a constitutional amendment, which needs the approval of two consecutive sessions of the state legislature and approval by a public referendum. It’s an arduous process, but it’s doable; just last year, we amended our constitution to raise the judicial retirement age from 70 to 75 through the same process.

Fair Districts’ plan, which they’re hoping to get on the ballot in time for the next redistricting, would institute a much more impartial and restricted redistricting commission. Their plan would create a new eleven-member committee, consisting of four Democrats, four Republicans, and three unaffiliated voters. No one could be on the commission if they or someone in their family has been a politician or has worked for one within the last five years. The commission would have to redraw districts in compliance with the Voting Rights Act; would have to maintain compactness (i.e. as close to circular as possible); preserve communities of interest (e.g. no taking poor communities and dividing them up among wealthy suburbs); and preserve natural political boundaries as much as possible (e.g. county lines). But perhaps most importantly, they’d be forbidden from using voting data in their considerations, since knowing how every ward voted is the most necessary ingredient for nefarious gerrymandering.

If the plan sounds obsessively neutral, that’s because it is. Unlike Project RedMap or Advantage 2020, Fair Districts is strictly nonpartisan. They’re not trying to flip the state legislature or ensure a lasting Republican majority. They just want to make it more representative and more effective. Whether Republicans or Democrats end up benefiting is irrelevant, as long as the process is fixed. And, quite frankly, both parties have strong incentives to fix things this time around.

Democrats currently suffer from an abysmal lack of representation given that they outnumber Republicans statewide, and partisan redistricting could continue to make it worse. But a Democratically-controlled Supreme Court gives Democrats all the power they’ll need under the current rules to flip the tables and gerrymander Republicans out of their fair share of representation.

The Fair Districts plan is based on other commissions that are already in effect—and effective. Canada, Great Britain, California, and even Arizona all have nonpartisan redistricting commissions that draw fairer boundaries. According to Keith Forsyth, Fair Districts’ Philadelphia Coordinator, “If you read the research, there are a number of different metrics that measure gerrymandering, and Arizona’s numbers have gone down to nearly zero since they changed how they redistrict.”

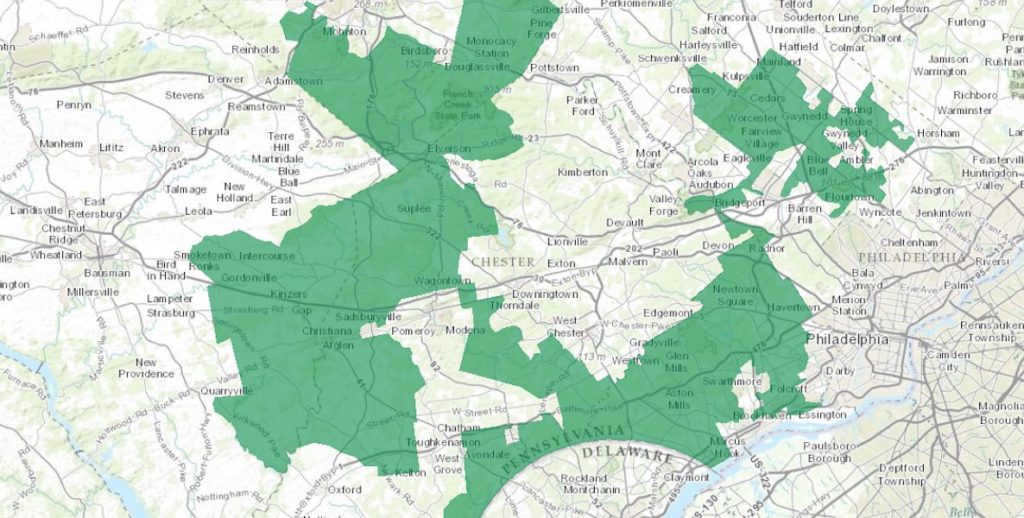

Although their plan seems like a no-brainer, not everyone’s on board. A decent number of Democrats favor their plan, like locals Daylin Leach and Pam Delissio, as do some rank-and-file Republicans. But so far, no support from Republican leadership. “They’re opposed to any change,” says Kuniholm. “Their position is that we already have a citizens commission: It’s called the state legislature. Legislators are elected by the people and therefore is already democratic.” Which, of course, is absurd, because a true citizens commission would never draw districts that looks like this:

Changing how we redistrict isn’t going to be easy. More legislators need to get on board, and that means that more voters of both parties (and Independents!) need to be calling their elected officials and demanding change. The fact that we have such a long constitutional amendment process means that reform needs to get off the ground in the next couple of years to take effect before 2021. If not, we’re looking at 14 more years—until 2031—of nonsensical voting districts that help no one but the politicians we let draw the lines.

“Citizens,” says Forsyth, “have better sense than the legislators do on this issue.”