Oh, shit. What now?

That was my first thought, seeing those flashing red lights in my rear view mirror. I could feel my heart starting to race. Pulling over, I took deep breaths, trying to calm my nerves. Here we go again.

I’m a Black man who drives a BMW in America, and I am, sadly, a veteran of this very situation. Since the killing of George Floyd, I’ve been pulled over four times by police. I’m a law-abiding Ivy League graduate, and a taxpaying citizen. I have insurance, no outstanding tickets, and two working tail lights. Of all the times I’ve been profiled—too numerous to count, through the years—not once has a traffic stop resulted in the issuance of a ticket. Yet I’ve been terrified each time.

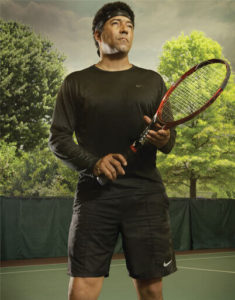

The most recent such stop came at 11:45 at night last month on Route 202 South. Once I saw those lights, I knew the drill. Pull over slowly. Move the tennis racket—I’m a professional coach—on my front seat to the back, not wanting to chance that an officer might mistake it for a weapon. Lower the windows. Turn the radio down. Dial my daughter; she wasn’t home, but her voicemail would record the encounter. Then place hands visibly on the steering wheel in front of me.

The officer, a state trooper, approached on my passenger side. I’m 59; he seemed more than half my age. And he was nervous, speaking fast, stammering. He asked if this was my car. “License and registration,” he commanded when I told him it was.

MORE ON RACE

I know by now to keep it short, to only speak when spoken to. I don’t even ask what I’ve been pulled over for because I don’t want to escalate the situation. “Do I have permission to unzip my jacket pocket for my wallet, sir?” I asked.

He nodded, watching me intently. I went slowly. My hands were shaking. I actually have a couple of my old expired licenses in my wallet along with my current, valid one, and I just handed them all to him. “You’re acting strangely,” he told me. I could hear the alarm rising in his voice.

“That’s because I’m terrified, sir,” I said. And it was true: I felt certain that I was about to be killed.

“Do you own a weapon?” He asked.

“No, sir,” I said.

“Have you been drinking?”

“Absolutely not.”

He looked at the licenses in his hands. “It’s against the law to save old licenses,” he said. “That’s a state law. You live in Pennsylvania, you should know that.”

Then he asked for my registration and proof of insurance. I explained that I keep them in my driver’s side door pocket. To reach them, I started to open my door. “Don’t open the door,” he said.

Suddenly, I became aware of another officer now on the driver side of my vehicle. “He’ll shine a light so I can see you get the license and registration,” the cop on my passenger side said, while the one on my side shined a flashlight in my eyes. As I reached down, the officer on my passenger side asked again, his voice more insistent now: “Do you have a weapon?”

What is rarely talked about when we talk about driving while Black is what it feels like.

“No sir, no sir. I do not have a weapon,” I said, moving slowly, trying to appear calm so as to calm him down.

Both officers returned to their squad car, where they no doubt saw my spotless record on their computer screen. When the officer returned to my passenger window, he handed my documents back to me. “You drove over the painted line in the middle of the road,” he said. “That’s why I pulled you over. We don’t just pull you over for nothing.”

“I’ve been pulled over many times for nothing,” I couldn’t resist saying.

“Well, we’re State Troopers,” he said. “We don’t do that.”

“Thank you for keeping the streets safe, officer,” I said, before going on my way.

What is rarely talked about when we talk about driving while Black is what it feels like. How emasculating it is to sit there and only speak when spoken to, to hear your own yes sir and no sir above the beating of your own heart, to have to simply pray that the authority figure in front of you has his wits about him, isn’t having a shitty day, and won’t fly off the handle. In every driving-while-Black interaction I’ve ever had, it’s as though I’ve been stripped of my humanity. I’m not someone who has played on the pro tennis tour, who has folks who love him, and who he loves. I’m just a Black dude in a BMW who must have a weapon in his possession.

The terror and the forced subservience of every encounter has long aftereffects. You’re frightened in the moment, exhausted afterwards, and traumatized forever.

It’s not lost on me how frightened the officer who pulled me over was. He didn’t know if he was about to be ambushed, just as I didn’t know if I was about to be the latest Black man unjustly killed by the police. The irony is that I respect the police, and I acknowledge the difficulty of the job they have to do in keeping us safe. But, in a lifetime of being stopped by them, I’ve never felt that respect directed back to me.

I became a tennis player because of the great Arthur Ashe. As the lone Black star in a lily-white sport, he carried himself in a way that was beyond reproach. He was all class. When I was a youngster, I went to see him play at the Spectrum. After his match, I approached him and asked for his autograph. He asked my name and signed a paper plate for me. Later, I would read his writings about race. Being Black in America, he once said, is like having a second full-time job.

I think about that every time I get pulled over. The terror and the forced subservience of every encounter has long aftereffects. You’re frightened in the moment, exhausted afterwards, and traumatized forever. I put in a lot of hours at work on the tennis court. When you’re done work, maybe you can relax. But when it comes time for me to get behind the wheel of my car and head home, I’m really clocking in on my second job, a job none of us asked for, or deserve.

Eric Riley, the former captain of the University of Pennsylvania tennis team, was the 369th ranked player on the ATP Tennis Tour and has coached pro players like Lisa Raymond and Pam Shriver, as well as weekend warriors. He can be reached at teamrileytennis.com

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who stipulate to the best of their ability that it is fact-based and non-defamatory.