Cresheim Village Neighbors is a 36-year-old neighborhood association that’s unlike most neighborhood associations. One reason: The neighborhood itself is unlike most Philly neighborhoods, full of mature trees, Wissahickon schist twins, brick sidewalks, rainbow flags, a devotion to diversity and PhDs who work in social services. The other reason: Steve Stroiman.

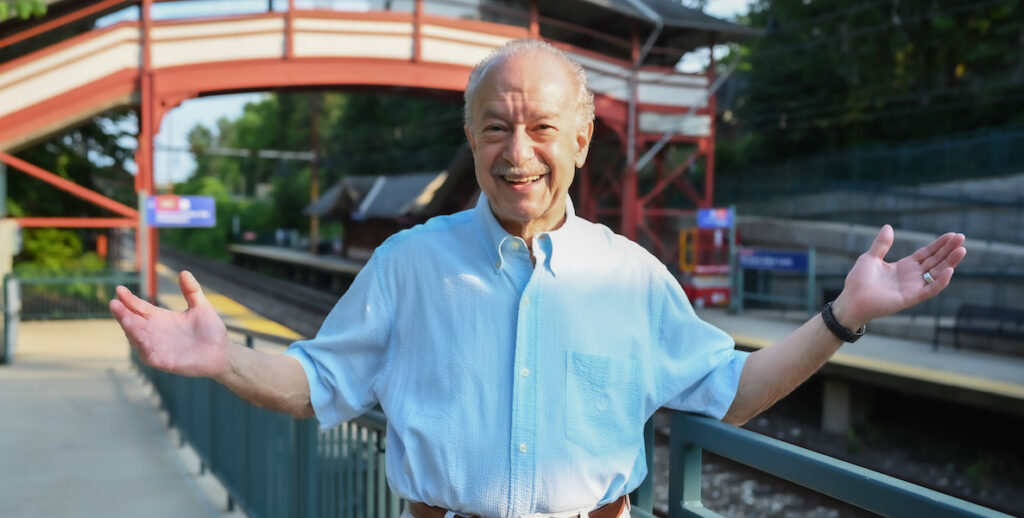

Stroiman, a retired teacher and rabbi, helped found Cresheim Village Neighbors (CVN) in 1988 and has since functioned as the group’s convener, mediator, municipal and state liaison, welcome wagoneer and most visible member. But don’t call him CVN’s leader. The 79-year-old prefers “coordinator by default.” He also refers to himself as “a foot soldier,” and the hub of a wheel “with many spokes.”

“Steve has a real gift for bringing people together. He has a gift for listening to people to find out what their needs are. And, he’s not too arrogant to think he knows everything.” — John Colgan-Davis

He’s not just being modest. From the start, CVN has eschewed hierarchy or formal designation. The group, he says, is “officially a non-nothing. After 36 years, you would think we’d apply to be a 501 (c) (3) or whatever it is. But we don’t have dues; we don’t pay for banking …”

But even — maybe especially — without a title, Stroiman is a shining example of not just how to bring a neighborhood together, but also how to get things done there. Sheila Erlbaum, a resident of 46 years, writes, “He knows everyone and is involved with everything that makes our community vibrant and special … Steve helps create the change that makes our neighborhood the place you want to live in — and never want to leave.”

Those of us stumped about how to deal with our own neighbors or local officials or even family members should take a page from Steve Stroiman’s book.

(But not literally: He’s been working on a novel about Moses returning to earth as a guest on a failing talk show for years.)

The people in the neighborhood

Cresheim Village Neighbors’ purview — because “Cresheim Village” isn’t an official neighborhood that you can find on Google maps — lies between East and West Mount Airy. Its semi-official boundaries are the unit and 100 blocks of Mt. Airy Avenue, Nippon Street and Durham Street, and the 7100 and 7200 blocks of Bryan Street and Cresheim Road.

Stroiman describes CVN’s borders as somewhat “porous.” After all, this is Mount Airy, the place a young Holly Robinson Peete thought was the model for Sesame Street (Robinson Peete’s dad was a producer and the original Gordon). Residents value their closeness, but welcome just about everyone. They’re also, says Stroiman, “probably the most progressive neighborhood in Philadelphia.”

He jokes that he used to introduced a neighbor — and “right-hand person” — by saying, “‘I want you to meet the Republican in our neighborhood,” he says. He also tells a joke about having to meet two out of three requirements to reside in Mount Airy: Wear flannel year round; wear Birkenstocks year round, and listen to folk music. A classical music fan, Stroiman makes the cut with two.

But, he insists, Cresheim Villagers are not monolithic in their beliefs. “We have diversity within a progressive framework … along the spectrum from liberal to very progressive,” Stroiman says.

His neighbors’ differences of opinion over Israel and Gaza recently led CVN to spend weeks researching and agreeing on a new policy for sharing non-neighborhood-related messages on their 450-address listserv, the group’s virtual town hall. Rather than ban all controversial discussion, the group decided members should type “partisan content” into the subject line of select emails — so that, Stroiman says, “If somebody doesn’t want to read it, they don’t have to.”

Problem solved. If only family members with differing political opinions did the same thing, think of how much more pleasant Thanksgiving dinner would be?

The Mount Airy-a

CVN began as a town watch. As the group welcomed more neighbors, they added more street names — Nippon, Bryan, Cresheim, Durham until the name grew so long that, “if we had stationery, it wouldn’t even fit,” says Stroiman. So, they settled on calling themselves a “village.” The town watch part didn’t last long, either. “We didn’t have enough crime,” he says. That’s not to say the neighborhood was or is entirely without safety issues.

About 15, 20 years ago, Stroiman was part of a small group of villagers who stationed themselves in lawn chairs across Germantown Avenue from men they suspected were dealing drugs. There was never a confrontation, but one of the alleged dealers crossed the street to ask what they were up to. Stroiman told him, “‘We are the Mount Airy beautification project, out here looking to improve the facades along Germantown Avenue.’” (Stroiman says the guy knew he was fibbing.) “We did this once a week for five months — until they left.”

Later, when a handful of young teens were, he says, “knocking off vases and pots on people’s porches, terrorizing senior citizens and trying to make life difficult for the lesbian couples — of which we have many and very proudly,” CVN gathered a list of nearby youth activities and groups and had a police officer go to the kids’ homes to warn their families if PPD received any more complaints, there would be arrests. Another problem, solved.

Every story he tells — the brilliant neighbor with mental illness who began deteriorating when his caregiver parents died; the time mail wasn’t getting delivered; a proposed residential redevelopment of an old bank and an Allens Lane bridge revamp whose designs risked clashing with their surroundings; an older couple who got mugged — Stroiman was there, with solutions.

(Those solutions, order: CVN found space in a nearby assisted living facility for the man and reunited him with his estranged brother, who sold the family home to pay for the care. For the mail, they brought Dwight Evans to an association meeting; Evans got in touch with USPS, who fixed things in a week and turned the case over to the FBI. Resident architects collaborated with the City and the private developer to redesign the bridge and the still-in-progress housing. And, their 14th District police captain sent a PPD representative who specializes in helping seniors who’ve been crime victims to the home of the couple — and then followed up with Stroiman to make sure they were doing OK.)

Of course, CVN’s solutions don’t always work. A certain persona non grata landlord won’t let the group replant the trees on his property that got dug up when he was having the plumbing redone for his aging apartment building. SEPTA is still planning to abandon the beleaguered West Chestnut Hill regional rail line, impacting both residents’ ability to get around and their beloved High Point Cafe at the Allens Lane Station, which Stroiman refers to as their “village square.” They’ve got parking issues — Erlbaum calls finding on-street spots “a competitive sport.” Also, longtime neighbors feel powerless to stem the area’s slow losses of diversity and affordable housing.

But they’re working on it, with creative thinking, dogged communication and a non-leader who is a masterful connector.

City Hall on speed dial

“Steve has a real gift for bringing people together,” says John Colgan-Davis, a retired teacher who’s lived on Mount Airy Avenue since 1993. “He has a gift for listening to people to find out what their needs are. And, he’s not too arrogant to think he knows everything. He can ask for help; he can ask for feedback. Those are all very important qualities in helping to hold a neighborhood together.”

The day after Colgan-Davis and his late wife relocated from Germantown, they found a carrot cake and a card that said “Welcome to the neighborhood” between their screen and storm doors. That was likely Stroiman’s doing. These days, Stroiman welcomes newcomers with a gift card to High Point Cafe. When a resident loses a loved one, he makes sure they receive a bouquet from the neighborhood florist. He also personally visits new businesses and invites them to the next association meeting, offering an opportunity to attract new customers and build goodwill.

“I have to say to myself, How can I keep communication open with the adversary? Because if you shut down communication with the adversary, you have none, right? I have to listen.” — Steve Stroiman

“I like to highlight good being doing good things,” says Stroiman. He’s invited the 14th District’s police captain — who seems to change every couple of years — both to meetings and to the annual June block party. He stays in touch with Cindy Bass, their City Council rep, who calls Steve a “great guy and great friend.” (Pro tip: Stroiman suggests phoning, not emailing, Philadelphia city officials; they’re more likely to return a call than an email.)

He’s gotten the streets commissioner to speak with the group; Stroiman and the district’s traffic engineer regularly exchange emails. So, when a big pothole on a narrow block of Bryan Street was scraping the bottoms of neighbors’ cars, he made a call. “Within maybe three hours, they had a crew coming out to fill it.”

If you live in Philadelphia, you know this is a truly extraordinary turn of events. Even more remarkable: When Stroiman noticed the repair was failing — the asphalt didn’t stick; the seams weren’t sealed — he called again. The next day, Streets sent out a crew and got it right.

These are small things, he says, but they’re important if they’re impacting you or neighbors you care about.

And, lest you think all this goodness comes with a hefty price tag, think again. Each year, CVN applies for a Philadelphia Activities Fund grant. They typically receive anywhere from $500 to $2,500, but usually $800 or $1,000. Stroiman says most of the money goes to their neighborhood elementary school — Houston — and High Point Cafe. Last year, they donated a chunk to the Chestnut Hill West Save the Train campaign. Otherwise, the funds mostly go to copy paper for the newsletter that the nearby Elfant Wissahickon office prints and Colgan-Davis oversees the delivery of to 300 households. (Like any smart neighborhood group, they recognize not everyone has or reads email. Also, Stroiman recently arranged for high school-age neighbors to receive school credit for helping with delivery too.)

A mensch of Mount Airy

Stroiman delegates, too. After all, he’s busy working on that novel, still convenes a group of Jewish spirituality seekers, and stays in touch with former students from his 34 years teaching Jewish studies at Barrack Hebrew Academy (formerly Akiba), a Jewish day school in Bryn Mawr. Among his former students, some of whom he connects with from time to time: future Gov. Josh Shapiro, future CNN journalist Jake Tapper and future Scrub Daddy inventor Aaron Krause. When he taught, he always insisted his students call him “Steve.” “When you work with teenagers, you have to be genuine,” he says.

Genuine, but tempered. That landlord who wouldn’t let CVN replant trees? Stroiman’s the only neighbor he’ll speak with.

“I have to say to myself, How can I keep communication open with the adversary? Because if you shut down communication with the adversary, you have none, right? I have to listen. So, when he demeans my neighbors and says he doesn’t want anything to do with them, I don’t respond,” he says, “If I get upset with someone, I have to maintain my composure and treat that person with respect.”

It’s not always easy. People get fired up over stuff. He’s been called names. When a neighbor lashed out with a particularly vicious slur, he responded with love. “She was hurting,” he recalls. “I wanted to give her a hug.”

Not everyone would do such a thing. Not everyone is Steve Stroiman.

Correction: The neighborhood association’s name is Cresheim Village Neighbors, not Cresheim Valley Neighbors.