Towanda Tynes, a 47-year-old Air Force veteran who lives in the city’s Fairhill neighborhood, has developed a habit, that even she acknowledges is a symptom of what ails our politics these days: Tuning out her neighbors.

“I do not engage with people who want to have a conversation about our political situation who don’t vote,” Tynes says. “I believe in voting. And I feel like they have no business talking about what they don’t like if they don’t participate.”

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.In Fairhill, an area of North Philly roughly bordered by Lehigh and Allegheny avenues, 5th Street and Germantown Avenue, those people who don’t vote are plenty. In last year’s election, turnout among registered voters was low in a city of low voters, at just 12 percent. In 2015, when the city elected Jim Kenney to be Mayor, just under 16 percent came out. And that’s among those who are registered; many of Tynes’ neighbors, and residents throughout Fairhill, haven’t even taken that step.

![]()

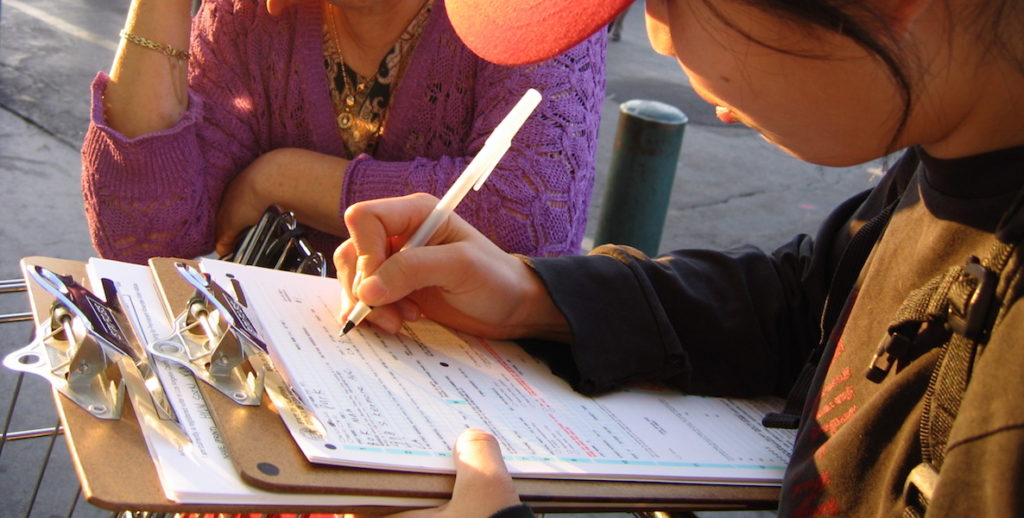

Over the next few weeks, Fairhill Neighbors will send volunteers to 19 different spots around the neighborhood, and door to door, to register people to vote. (Tynes says they are looking for volunteers to help with this effort.) Along the way, they hope to encounter enthusiastic voters who they can then recruit and educate to be Voting Champions. With the election just two months away, Tynes says she knows this could be hard to pull off in a way that makes a sizable difference for the primary. But she also knows there is no time to wait.

To a large degree, political engagement efforts have been removed from farther flung neighborhoods most in need of political change—those with high poverty, large numbers of minorities and immigrants, and historically low voter turnout. Fairhill’s Voting Champions initiative is an effort to fight that inactivity.

“I can’t afford to write people off,” Tynes says. “People can have a change of heart. There are so many disgruntled people out there about our political situation. Now is a good time to round up some of those folks and try to get them involved.”

![]()

But to a large degree, those efforts have been removed from farther flung neighborhoods most in need of political change—those with high poverty, large numbers of minorities and immigrants, and historically low voter turnout. Fairhill’s Voting Champions initiative is an effort to fight that inactivity, to bring more people into something that only works when more people are involved—democracy.

“A lot of people really care about the neighborhood,” says Denise Anderson, one of the founders of Fairhill Neighbors. “But they are burned from being the only people cleaning up their block, or getting involved. We’re trying to raise up the next generation of neighborhood leaders.”

Fairhill Neighbors formed a couple of years ago, when four different grassroots groups got together to do a survey of community needs and assets. That has grown into a neighborhood-led coalition of old and new residents, who now meet monthly to share information, and organize monthly events, like cleanups or a backpack giveaway at the local Julia de Burgos elementary school.

“If I expect any kind of change, I really need to step up my game as a citizen,” Tynes says. “And that’s what I’ll tell folks: It doesn’t begin here or end here when you push that button to vote. That’s a part of the process. You have be engaged far more than that if you want to see a change.”

Anderson and her husband—who both work for Servant Partners, a Christian community organizing group—moved to Fairhill four years ago from nearby Kensington, directed by the “Holy Spirit” to do neighborhood ministry in North Philly. They fell in love with their new community, which Anderson describes as “a place of surprising peace,” despite continued violence. “There’s a sense of community here that there isn’t elsewhere,” she says, a contrast to living near the drug chaos near Kensington & Allegheny.

Anderson is white, college-educated and in her 30s, as is her husband. They are the only new residents, and only white ones, in Fairhill Neighbors. The rest are a mix of African American and Latino, just like the neighborhood. The initial group spread the word about meetings by posting and delivering hundreds of fliers—including one that Tyne got in her mailbox—and now has a core group of 20 to 25 regulars who show up every month.

At a meeting early this year to decide what their spring projects would be, they decided to do something around voting. Later, Anderson says she was talking about this with someone outside the local library, when a woman overheard them and interjected. “I’m the one who drives around and picks everyone up, and takes them to the polls,” she said. That triggered the idea of a Voting Champion.

The biggest challenge now is registering enough people by the April 16th deadline, and recruiting enough Voting Champions—especially with just 25 regular Fairhill Neighbors members—to make a difference. The group also plans to throw an election eve block party, to get people excited about voting, and to celebrate people who show up at the polls via Instagram.

Tynes, who says she knows most everyone on her small block of Darien Street, plans to be a Voting Champion herself—a reversal of how she’s been coping with the political situation for the last couple of years. She’ll knock on doors, engage her neighbors in their political griping, and remind them that they have the power to make a difference—especially in their own small corner of the world, in the type of election that most matters: Local.

“If I expect any kind of change, I really need to step up my game as a citizen,” Tynes says. “And that’s what I’ll tell folks: It doesn’t begin here or end here when you push that button to vote. That’s a part of the process. You have be engaged far more than that if you want to see a change.”