The block of Kensington Avenue between Tioga and Atlantic is a fairly moribund commercial strip. On one side of the street, there are two empty lots, some houses broken up into apartments, a couple of businesses, including a longtime supplier of power washing equipment, and often a lot of trash; on the other, another empty lot, and a few storefronts continuously shuttered with metal grates. It is not an inviting entry point to a neighborhood that struggles to make itself a destination for people to live, work and spend their money.

But this summer, the block will experience one small shift in its character, a potential spark to a much-needed change. At 3525 Kensington Avenue, right in the middle of the block, Sherimane Johnson will open Naturally Sweet Desserts, a vegan cafe and bakery that will deliver all over the city and be open all day for local residents. Johnson knows—even with a colorful awning and bright lighting—her cafe might not get a lot of consumer street traffic. But she also knows you have to start somewhere.

“If you’re saying there’s a renaissance in the neighborhood that has to include the Avenue,” Sourbeer says. “The challenge allowed for group momentum, as opposed to coming in alone. You don’t have to be a pioneer all on your own, because there are nine businesses involved.”

“My business is not dependent on people walking in the door,” Johnson says. “But I think they will. Good food has a way of clearing your mind and making you feel empowered. If you start to feed people better, they can change their circumstances.”

Naturally Sweet Desserts is one of nine new businesses set to open this year on a stretch of Kensington Avenue, from F Street to E. Venango, scattered points of new commercial life in a strip literally in the shadow of the Market-Frankford El. They were the winners late last year of the Kensington Avenue Storefront Challenge, an initiative by socially-conscious developer Shift Capital to bring sustainable, community-minded businesses into the area. The businesses, which each won up to $10,000 in renovation and up to a year’s free rent, include restaurants, bakeries, cafes, a glass blowing studio and a 24 hour daycare facility.

The project was part of Shift’s larger vision for the area of North Philadelphia—a few blocks wide, but spanning the length of four El stops—where the company owns just under 2 million square feet of property. Founded in 2013 by Brian Murray, a former PriceWaterhouseCoopers accountant-turned-impact real estate investor, Shift has a unique model for a commercial developer in Philadelphia: To create socially, environmentally, and culturally-conscious commercial and residential spaces that consider the needs of the neighborhood, as well as the profit margins of the business.

![]()

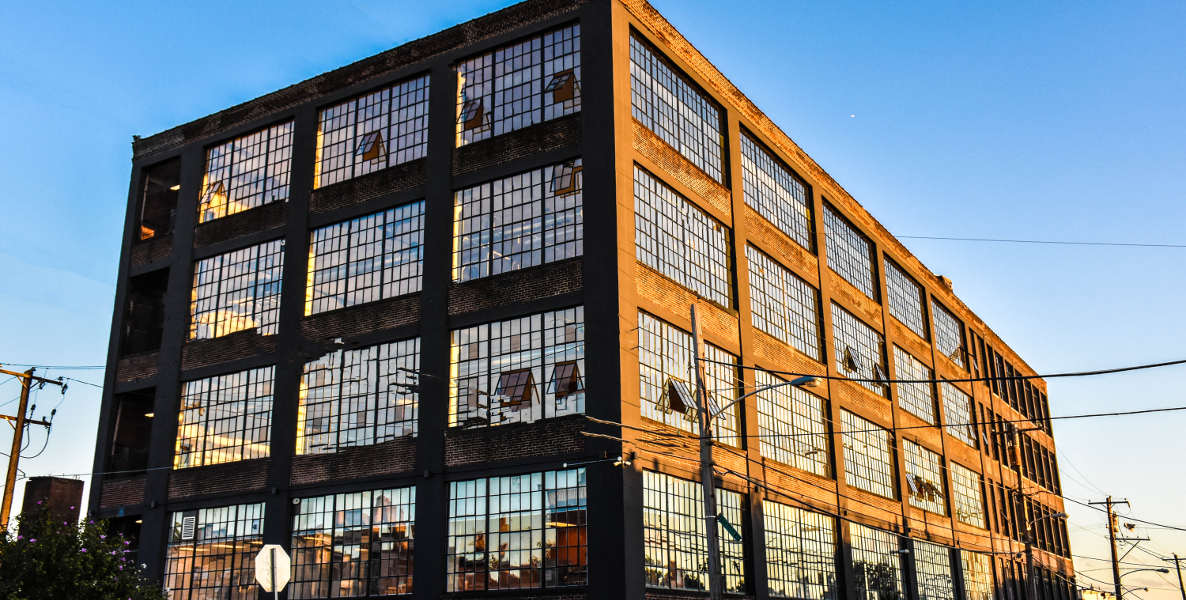

Most of Shift’s investment is in former industrial buildings that until a few years ago were mostly empty shells, the remains of the manufacturing hub that used to power Kensington. Its Maken Studios—for “Made in Kensington” opened in 2015 with 700,000 square feet of studio and office space, including the local prep area for Austin-based SNAP Kitchens, which employs 80 people, the vast majority of whom can walk to work; Sourbeer says the company may be expanding its operations to encompass Baltimore and DC.

“I didn’t want to be a business that moves in and adds to the problems of gentrification,” Johnson says. “The fact that I can be part of a build-up of a neighborhood instead of a relocation of folks, makes me feel less like part of the problem, and more like part of the solution.”

Shift also owns 120 single family homes nearby, which it renovates and rents at the neighborhood’s market rate. Over the last few years, it acquired the commercial spaces along Kensington Avenue as they came up or seemed to fit part of a long-term vision of shaping a neighborhood where people want to work, live and spend their free time. But figuring out how to transform the once-bustling commercial strip proved a conundrum far greater than Shift, with its handful of properties, could take on—until they decided to open it up to everyone.

Shift launched the storefront challenge in September, along with the city’s Commerce Department, and two local non-profits, Impact Services and the New Kensington Community Development Corporation. By the November deadline, 30 businesses from around the city had applied for the nine open storefronts; 14 were selected to participate in a Shark Tank-like competition in early December that hinted at what a vibrant commercial corridor could be. “It was so compelling, and they were so excited, that it was contagious,” Sourbeer says.

Each entrant had five minutes to impress a panel of judges, including local community leaders, Council people, civic association members, Shift and its partners. Kensington resident Genevieve Geer, a glassblower, and her husband, a metalworker, brought in a metal “pegacorn” that breathed fire, and spent the time making smores for the panelists while they talked about Juggarnaut Studios, their idea for a shared artists studio space, glassblowing facility, event space and craft retail shop. The entrepreneurs behind Caphe brought mason jars filled with condensed milk and their specialty Vietnamese coffee; Johnson brought in samples of her plant-based desserts, to prove they are delicious in addition to healthy.

The nine winners were selected based on viability, finances, how well they would fit into the community, the applicant’s background and motivation, as well as a mix of ideas that ranged from arts to food to practical. One idea, a 24 hour daycare to provide childcare for folks who work the night shift, is an example of how Shift’s approach to finding tenants made a difference: Murray and Sourbeer both say it never occurred to them that there was such a need until they learned about it through the challenge.

In addition to the renovation and rent money from Shift—negotiable for each business—the winners are getting help in drawing up their business plans, applying for loans, and navigating city departments from the nonprofit partners. The Commerce Department, as part of its storefront improvement program, is providing $5,000 plus 50 percent of costs up to $10,000 for outside renovations; and another $5,000 towards the cost of installing security cameras.

Of course, the really hard work for the entrepreneurs begins now. So far, all the businesses are on track to open this year. Opening any new business, in any part of town, is a calculated risk. But most of Shift’s storefronts, like the one Johnson is moving into, are lone outposts in long blocks that do not welcome the casual shopper. The businesses are not alone, exactly; but they are not clumped together like those that came up on Frankford Avenue in Fishtown, or in East Passyunk several years before. They are like pinpoints in the vast fabric of a street known, as Sourbeer points out, for drug use and sales—a reputation based on the reality of life in many parts of Kensington.

But perhaps the most resounding trait of these entrepreneurs—any entrepreneurs, really—is that they are undaunted. “I am not at all intimidated by the neighborhood because I come from something like that in the South Bronx,” Johnson says. “Sometimes I think that people think that because people are poor they don’t want more. The people I grew up with wanted more for their children—good food, education, clean water.”

Like Geer—a Kensington resident who is active in her community association, and always thinking about how to carefully improve the area—Johnson says she joined the challenge only after learning more about Shift, its mission and its hope for the North Philly neighborhood.

“I didn’t want to be a business that moves in and adds to the problems of gentrification,” Johnson says. “The fact that I can be part of a build-up of a neighborhood instead of a relocation of folks, makes me feel less like part of the problem, and more like part of the solution.”