The concept for The Long Ride Home: Black Cowboys in America was born from the ashes of the heroin epidemic in Philadelphia during the early 1980s. I had just come off photographing a yearlong documentary project for the Philadelphia Inquirer with my colleague, the unflappable reporter David Zucchino, covering the story, which I shot in black-and-white film, my preference then and now. Spending time in and out of heroin dens had taken its toll. I told myself the next story I worked on would be something joyful and shot in color.

The idea of a project on Black cowboys had been in my mind for a while. I took a month or so break before pitching the idea to my editors at the Inquirer. They responded, “Why Black cowboys? Why not other ethnic cowboys?” The answer is a complicated one and only easily understood if you feel you’ve been denied a vital part of your history. After several discussions, they relented and let me pursue the story.

The photo essay ran as a cover story in 1992 in the now-defunct Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine. After its publication, I received more mail (handwritten, customary in those days) than I had ever received for any story, even the drug story, which ran the year before as an epic five-part story with fifty-three images plus a photo essay in the Sunday magazine.

A Brief History of Black Cowboys

The origins of Black cowboys were in eastern Oklahoma and eastern Texas. When slavery was practiced in the Indian Territory and Oklahoma (prior to Oklahoma achieving statehood in 1907) and in the Republic of Texas, enslaved Black men worked cattle in both regions. In the antebellum Southwest, in the Indian Territory and in Texas, Black slaves worked large ranches. After the Civil War in the United States, many cattle roamed freely around the state of Texas. There was a request for good beef in the Eastern markets and ranchers in Texas saw a golden opportunity to make good money. The Black men who had worked on the ranches as slaves were hired as wranglers, herdsmen, and cooks for the cattle drives to the railheads in Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. It has been estimated that at least one-fifth of all the men who herded cattle on the great cattle trails leading out of Texas were African Americans. Sometimes, the whole cattle crew would be comprised of Black men.

After the Civil War, former slave owners in Texas and in the Indian Territory hired freedmen to work their livestock. Many of these cattlemen recognized the skills and value of Black cowboys. In many of the Works Project Administration (WPA) slave narrative interviews some Freedmen remained with their former masters to work cattle and others were employed by different cattle ranchers.

The Modern Era

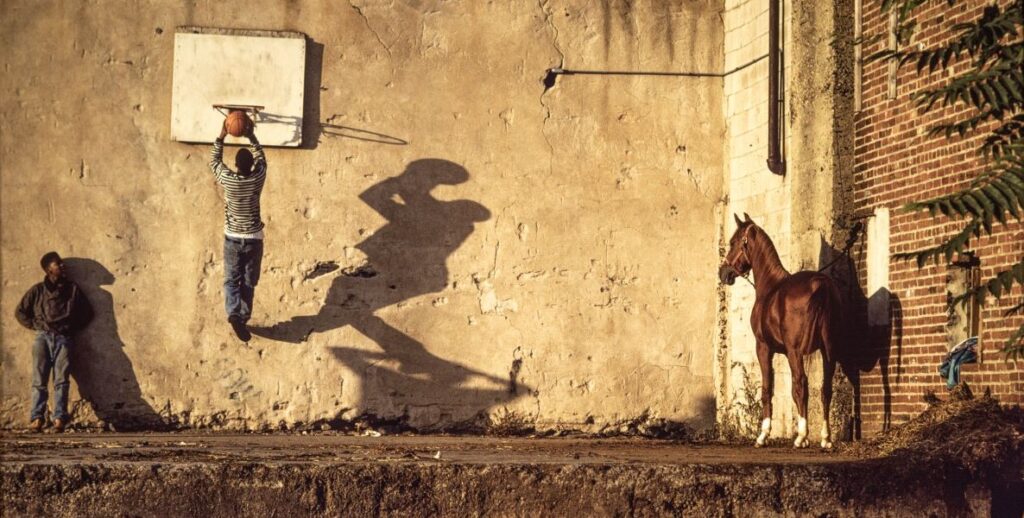

Black cowboys started to appear during the 1960s in many urban, suburban, and rural areas east of the Mississippi River, inspired by the many television shows and movies set in the West at the time. Philadelphia has a long history of Black riding stables dating back more than a century of which the last remaining is the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club, founded in 1980 by Ellis Ferrell, Jr. This club inspired the 2021 film, Concrete Cowboys in 2021, which starred Idris Elba.

While fads come and go, the cultural significance of the subject remains. I believe my archive is one of, if not the most, extensive collections that covers the breadth of African Americans who share a Western heritage—more than 7,000 transparencies portraying not only dozens of individuals but the beauty, romance, and visual poetry of this lifestyle. It is my hope that this book affirms today’s thriving culture of Black-owned ranches, rodeo operations, parades, inner- city cowboys, and retired cowhands and inspires further conversation about what it means to be a cowboy — as well as what it means to be an American.

Excerpted from The Long Ride Home: Black Cowboys in America, copyright 2024 Ron Tarver. The Long Ride Home releases on August 31, 2024 and is available for pre-order here.

Ron Tarver, an associate professor of art at Swarthmore College, spent 32 years as a staff photojournalist at The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he shared the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for his work on a series documenting school violence in the Philadelphia public school system. He is a recipient of Guggenheim and Pew Fellowships, and has received grants and funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and two Independence Foundation Fellowships. During his time at the Inquirer, he was nominated for three Pulitzers and honored with awards from World Press Photos, the Sigma Delta Chi Award of the Society of Professional Journalists, the National Profession National Press Photographers Association/University of Missouri Pictures of the Year, as well as other national, state, and local honors.