It’s not discussed openly as much, and some consider the question either rude or offensive. But when it comes up it evokes all sorts of emotions and rankles many a nerve: Do community activists spotlighting police brutality and violence give the same attention to rising homicides or “proximal” violence in troubled Philly neighborhoods?

Or, in shorter bursts asked frequently by frustrated residents living on crime-ridden blocks: Where is Black Lives Matter when this happens?

For understandable reasons, it’s not the most delicate question. And many BLM activists, as well as supporters, get very twitchy when it’s asked; there are times when it could be easily construed as “blaming the victim” or wrongfully flipping accountability at those either suffering from law enforcement violence or the ones struggling to stop it through constant protest. But, it is asked quite a bit—and not just in Philly and not just by snarky white people. Many major cities dealing with rising violent crime rates and homicides find that same question bubbling up when fearful black residents look to well-branded causes like the nationally-renowned network to lend a helping hand. Even elected officials representing those communities quietly ask the same thing, although carefully, out of fear they’ll unleash social media fury.

We asked that question on Reality Check in recent weeks, and took in calls from, once again, anxious residents and WURD listeners who wondered out loud why non-stop shootings in Philly neighborhoods weren’t getting the BLM personal touch the same way police shootings were. The feeling was that community activists rushing to highlight trigger-happy officers should be able to “walk and chew gum” and offer equal air and social media time with respect to the burgeoning crisis of rising gun violence. (Many, by the way, still call that the antiquated “black-on-black crime”—but, we’ve banned that term on Reality Check because it’s awfully racist and patently inaccurate based on pure data: If you are the victim of a crime, the perpetrator will more than likely look like you because of geographic proximity.)

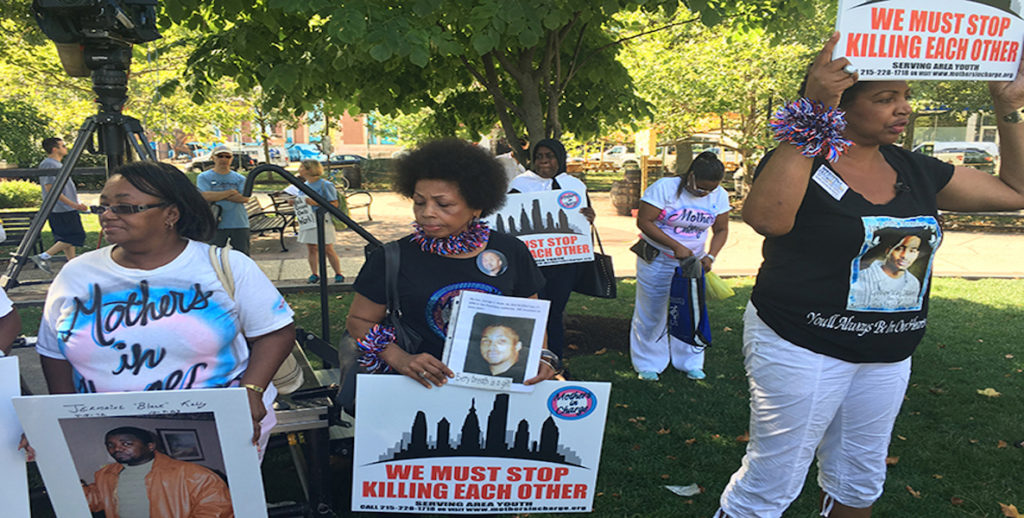

Black communities are facing a public safety crisis on two fronts that are inextricably linked: police and “proximal,” both requiring coordinated and equal response. It’s just as offensive to the people who live in impacted neighborhoods when they’re pleading for a spotlight on that violence and get dismissed by policymakers and political leaders and leading community advocates.

When producers reached out to Black Lives Matter Philly for a needed and intelligent discussion on that question, group representatives tragically bailed from the scheduled segment at the last minute. However, Black Lives Matter Movement PA (same cause, different organization) founder and lead Asa Khalif eventually stepped in to discuss both topics: the need to continue that fight against police violence while simultaneously fulfilling the need to improve public safety in troubled city neighborhoods.

Khalif’s first and foremost concern for the segment was the recent fatal shooting of David Jones, a 30-year old black man, by a 12-year veteran of the Philadelphia police force—in the back, while he was running away from the officer. Khalif found the police account of events suspect and the circumstances around the incident “yet another example” of law enforcement’s flagrant violation of a black civilian’s human rights. “And this wasn’t the first time either,” explained Khalif, pointing out how that same officer, Ryan Pownell, did the exact same thing back in 2010—shooting and paralyzing another black man in the back.

Interestingly enough, the discussion with Khalif was prefaced the day before with a segment featuring Upper Darby Police Chief Michael Chitwood during the Reality Check “Citizens” episode in conjunction with The Citizen. A police veteran for nearly 53 years in numerous jurisdictions, Chitwood was straight up: “I hear this all the time, that police officers in stressful situations don’t know how to talk to people. You hire good people, but their emotions get in the way, especially in diverse communities.”

“Based on my experience,” he continued, “the majority of complaints I get over and over again is that police officers don’t know how to talk to people. There is a customer service component that just doesn’t exist. Police need to be able to communicate—treat everybody the way you yourself want to be treated.”

One wonders if the two segments should’ve been blended into one. Maybe next time …

Meanwhile, while Khalif stressed the call to spotlight the Jones incident and for the dramatic overhaul of Philadelphia police engagement procedures, he also acknowledged the battles taking place on a two-front war against police violence and struggles with violence in the community or “beefs” as they’re often called. “This is very hard work,” said Khalif. “We are out there in the streets, in the community risking ourselves and doing everything we can to stop the violence, although it’s not something we broadcast and it’s not something media outlets are spotlighting.”

Do community activists spotlighting police brutality and violence give the same attention to rising homicides or “proximal” violence in troubled Philly neighborhoods? Where is Black Lives Matter when this happens?

According to Khalif, they’ve been on that grind, relentlessly working to resolve senseless neighborhood beefs before they reach the escalation point of no return—but, with limited resources and time, and not mentioning the personal risk assessment, there’s only so much they can do.

Black communities are facing a public safety crisis on two fronts that are inextricably linked: police and “proximal,” both requiring coordinated and equal response. It’s just as offensive to the people who live in impacted neighborhoods in places like Philly, DC, Baltimore, Chicago and elsewhere who are direct/indirect victims of violence/structural hostility/bullying when they’re pleading for a spotlight on that violence and get dismissed by policymakers and political leaders and leading community advocates.

Collectively, we shouldn’t be ashamed to have that conversation, we should be aggressively engaging and solving it. For example: Democratic DA candidates rightfully staked out positions on criminal justice reform, police brutality, and the like. But, there wasn’t spirited discussion on basic public safety issues, which is the basic job of a city prosecutor: keeping the citizens safe. Ultimately black urban or suburban neighborhoods and communities should be just as safe to live in as any other demographic; violence in the places we live shouldn’t be a norm. It’s bad enough black residents are battered by lack of socio-economic mobility and the inability to find affordable housing. That doesn’t mean they should be stuck in unsafe, violent conditions because of that and then told “your concerns don’t matter at the moment because we’re focused on this issue over here.”

Both challenges are very connected—and that connection can be an uncomfortable discussion for all parties. But it is a discussion that many are rightly demanding.