Shortly after completing his sentence in federal prison for drug offenses, the Reverend Christobal Kimmenez came face-to-face with the boy who fatally shot his 14-year-old son, William, three years earlier. The unexpected encounter took place in the Maryland juvenile detention facility where the shooter, who was 12 at the time of the slaying, was locked up.

Kimmenez, 63, spotted the boy among the young offenders he had been invited to preach to that day in 1998. “He didn’t know I was coming, and I didn’t know he was there,” he said. His initial impulse was to get close enough to hurt his son’s killer. Instead, he leaned on his religious convictions and suppressed his anger.

[This story originally appeared in The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for its newsletters here.]

Kimmenez said he told the boy that he knew who he was and forgave him. “That was a huge weight lifted off, and he and I began corresponding and talking,” said Kimmenez. His grace toward his son’s killer was aided in part by his knowledge that the boy’s father was doing life for murder, and that he himself had not been the best father to William. At the time, he didn’t realize that he and the young shooter had begun the process of “restorative justice” — a criminal justice approach designed to rehabilitate offenders through reconciliation with their victims.

In Philadelphia, the violence and crime that has plagued many communities for generations has given rise to a subculture of advocates and activists committed to stemming the bloodshed. Some speak on behalf of victims. Some focus on addressing the needs of perpetrators to prevent them from offending again. Still, others, like Kimmenez, speak for both victims and ex-offenders. His three-and-a-half year prison stint and the loss of his son have given him the perspective needed to do the work that he does, like convening restorative justice meetings between offenders and victims for the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office.

“The reason shootings have gone down in recent years is because we spent 2022 and 2023 investing in community-based alternatives to violence. These were not law enforcement investments.” — Reverend Christobal Kimmenez

A native of Washington, Kimmenez became a U.S. Marine at age 17, served in combat in Grenada, Panama, Kuwait and Somalia, and retired in the 1990s after he was injured in a car accident. He said he became addicted to drugs he used to manage the pain from his injuries, which led to his arrest at Washington National Airport when authorities found a stash of drugs on him. Shortly after being released from prison and completing drug rehab, his son was murdered.

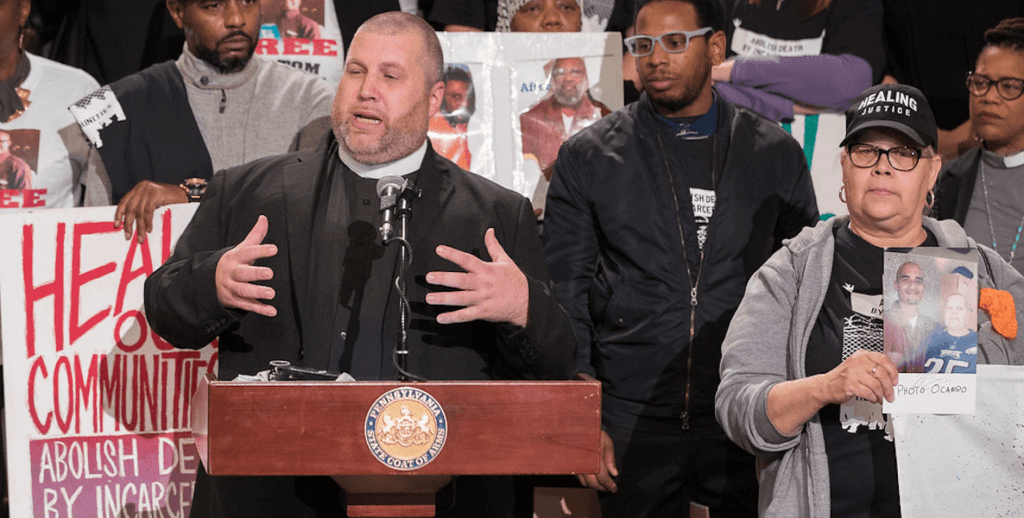

Kimmenez then moved to Philadelphia for a fresh start, and to be close to his wife’s family. He became an ordained Baptist minister in 1996, and is now the associate pastor for social justice at the People’s Baptist Church in Southwest Philadelphia. He is also the executive director of Healing Communities PA, a faith-based prison reentry organization that advocates for those affected by crime and mass incarceration.

The father of six and grandfather of 12 said that since 2020, his Healing Communities organization has had a contract to help run the restorative justice program for the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. Data shows that people served by the program have an average recidivism rate of 19 percent compared to 56 percent of those who went through traditional prosecution, Kimmenez told the state House of Representatives Judiciary Committee in April.

“Don’t ever think that forgiving someone for putting your little boy in the ground is ever going to be easy, but it sure was freeing.” — Reverend Christobal Kimmenez

In late September, he helped organize a three-bus caravan to the first annual Survivors Speak March in Washington, D.C. Sponsored by Los Angeles-based Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, the march drew several thousand people from across the country. They called for greater services for survivors of crime and the formerly incarcerated, including restorative justice.

Robert Rooks and Lenore Anderson, co-founders of Crime Survivors, told those gathered near the Capitol Building that less than 10 percent of crime victims access states’ victim compensation programs and other government-funded services. “We need you now more than ever because we are seeing tough-on-crime come back,” Rooks told the crowd. “We’re seeing our loved ones used as political pawns. We’re seeing some of the same old strategies reemerge to justify the increase in incarceration.”

Fresh from his trip to D.C., Kimmenez sat down with The Trace for an interview. These answers have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

MD: You have noted that you are both a former criminal offender and victim of crime, having lost your son. Of those who you work with, how many have the same background?

CK: When you think about the amount of young people who end up in the system for gun violence, many have been physically abused and sexually abused themselves. A lot of that goes unreported. It’s not unusual that people who are in the system are also victims themselves. A lot of us are in the same family, we’re in the same community. In the last couple of years we’ve been trying to change the conversation around that. There’s been a lot of shame and guilt around victims who also have family members who have caused harm.

From your vantage point, what drives gun crime and other violence among the people that you work with?

The real cause of crime is poverty and centuries of disinvestment and redlining and exclusion and oppression and devaluation of Black and Brown lives. Wealthier suburban communities invest more in parks, rec centers, schools and health care. Communities that are adequately resourced experience less crime.

What became of the boy who fatally shot your son in 1995?

As a result of the restorative justice process with me, his life started to change. He was released at 21 and never went back. I don’t publicly reveal who he is because that’s his choice. But, he has a master’s degree, his own family, and he works with a group in L.A. that gets kids out of gangs.

Have you completely forgiven your son’s killer?

Forgiveness for me is greater than just letting him off the hook. Not forgiving and resentment is allowing somebody to have power over you. So, when a victim forgives and releases that anger and resentment, in a lot of ways you’re taking your power back. Secondly, forgiveness is a huge tenet of my faith. It’s hard to say that I’m a practicing Christian if I cannot forgive. It was the hardest thing I ever did. Don’t ever think that forgiving someone for putting your little boy in the ground is ever going to be easy, but it sure was freeing.

When you speak to offenders during restorative justice sessions, what messages do you convey?

We talk about the reality, not the romanticized stuff you see on TV, but the reality of what prison life really is. The reality of what life without parole looks like. Especially in PA where life does mean life. We talk about the pain that they cause their families, the pain that they caused their victims’ families.

What are your thoughts on homicides and shootings being down about 40 percent in Philadelphia so far this year compared to the same time last year?

The reason shootings have gone down in recent years is because we spent 2022 and 2023 investing in a lot of community-based alternatives to violence. These were not law enforcement investments. We’re making big strides towards reducing violence. We’re seeing more health and youth services and all of the things that go into evidence-based practices that make communities safer.

What are you hoping will result from the Survivors Speak March that you went to D.C. to participate in?

A lot of that march was about not only demanding restorative justice and second-chance policies, but also demanding better victim compensation, better rules and laws around victims being able to show up for court and not have their jobs penalize them, more relocation funds for witnesses and victims who have safety issues. And better reentry policies, also. We can’t expect people to come home from prison and stay out if our reentry policies are basically preventing you from getting a job, owning a home, or going back to school.

Mensah Dean is a staff writer at The Trace. Previously he was a staff writer on the Justice & Injustice team at The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he focused on gun violence, corruption and wrongdoing in the public and private sectors for five years. Mensah also covered criminal courts, public schools and city government for the Philadelphia Daily News, the Inquirer’s sister publication.

MORE ON GUN VIOLENCE FROM THE TRACE