She didn’t turn once to look at me.

She only watched in the mirror, with arched brows drawn over her layered eyelashes, as I tried each bathroom stall. We were two women alone in a restroom on the 10th floor of a city courthouse. Except for the hum of the fluorescent lights, it was silent until she said:

“Honey, none of them lock.”

She still wasn’t facing me, busy powdering her face. I noticed the dark purple rings under her eyes.

I sighed.

“Really? OK, thank you,” I offered up, with a smile that I knew twisted like the knots in my stomach.

It was early. My coffee hadn’t set in yet. And the courthouse—a bustling beehive of cops, court clerks, attorneys, judges, defendants and victims—was the last place I wanted to be. The courthouse, with all of its bright lights and badges, was the ultimate symbol of Philadelphia’s running-on-empty criminal justice system—one that has failed me.

“Doll, go in! I’ll hold the door for you while you squat!”

Lost in my head, I hadn’t realized she’d turned from her reflection and was now standing in front of me. Smiling and pretty, she was the Fairy Godmother of Broken Bathroom Stalls. I smiled genuinely—the first time that morning.

The duty of holding a broken bathroom door closed while you pee is an intimate one, typically reserved for best friends in a shitty bar. When it’s 8 a.m. in a courthouse, it’s a little awkward. Unless you talk.

In a twisted way, she was lucky in this situation. A judge would at least hear her case.

She told me all about why she was there that morning. One day, while riding the bus, a man was giving her the creeps. He leered at her in a way every woman is familiar with. When she got off, he did too. He followed her, punched her. Called her a bitch.

A camera, luckily, caught it on tape. Even more luckily, a detective called her back about her case—something that often doesn’t happen for women who are victims of crimes.

I listened quietly, told her I was sorry she’d experienced that. She thanked me. There was a sense of rehearsed tiredness in both of our voices: her, tired of hearing it; me, tired of bad things happening to people and having to say it.

Then the roles reversed. Bluntly, she said, “So who do you testify against today?”

I explained that I was actually there to report on a trial, and I could feel her deflate on the other side of the stall door. Not only was I a total stranger, I was one who couldn’t participate in her campfire ghost story session about past men still haunting us. Until I did.

I told her I understood how terrible the reporting process really was. How I knew the waiting rooms, with their garish-colored walls and vending machines filled with knock-off chips, felt like purgatory and hell simultaneously.

How every question a cop or detective asks you about what happened sounds like an accusation that you’re lying.

How you wake up every day after you go to the station hoping for a call about your case until it’s easier to accept that one will never come. It’s easier to accept a lot of raw pain when you experience things like we had.

In a twisted way, she was lucky in this situation. A judge would at least hear her case. But in my case, months later, the underwear I wore the night it happened was still stored somewhere in the police’s evidence locker—most likely never thought of or examined again. This negligent system had given my rapist a silent “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

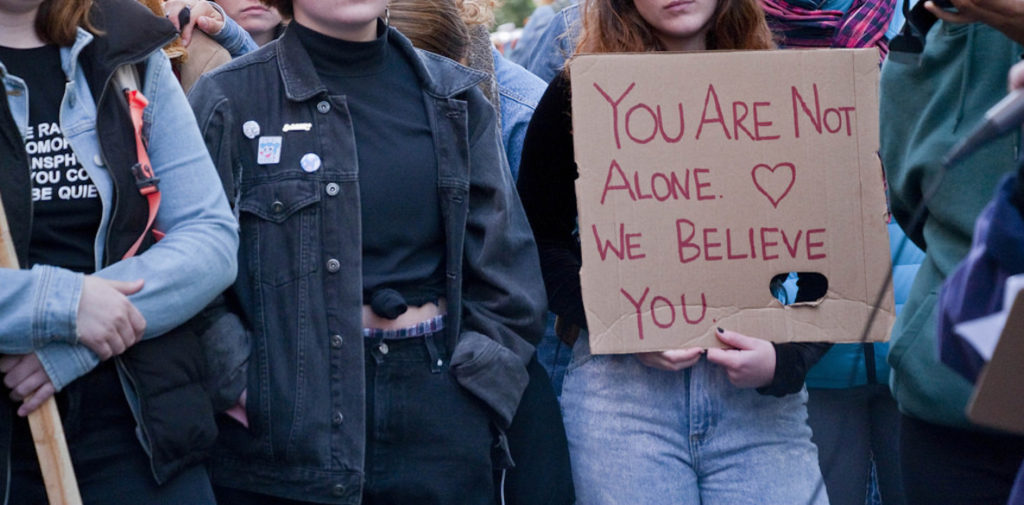

In that bathroom, we gal-palled about all the things that needed to be fixed in the criminal justice system. They couldn’t even give us survivors bathroom stall doors that locked. As we’re used to, we women fixed the problem our damn selves. Fixed the problem for each other.

I flushed the toilet, pushed the door open. We made eye contact for a fleeting second before she turned back to the mirror. I washed my hands and wished her good luck.

“Yeah, doll,” she said, too busy padding her face with makeup again to look my way.

After all, she had a man to see. And put away.

This story originally appeared in The Temple News on Feb. 19, 2019.