Alan Butkovitz’s mic drop landed with a thud.

Late last year, the former City Controller who butted heads with Mayor Jim Kenney and his predecessor Michael Nutter over the publicity-fueled way he audited the city released a report on the first year of pre-K. Hardly anyone covered the findings. They were released a few days before Christmas, the time of year when news dies on arrival. The only online trace of the report’s existence, aside from the full version on the Controller’s website, is a short CBS3 story.

They were also released by Butkovitz, a problem in itself.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.City controller audits aren’t often conducted with the rigor of scientific study. But add the donation Butkovitz received from bottling magnate Harold Honickman last year, the rumor he’s mulling a 2019 mayoral run with soda industry backing, and his claim that Philly didn’t need a soda tax to fund pre-K, and any Butko report with even a tangential relationship to the soda tax is ripe for the charge of political opportunism. Yet a few issues found by Butkovitz in what was otherwise a glowing review of the pre-K program warrant concern. The Mayor’s Office responded by mostly pointing out the items it considered incorrect and reciting job growth and minority business numbers.

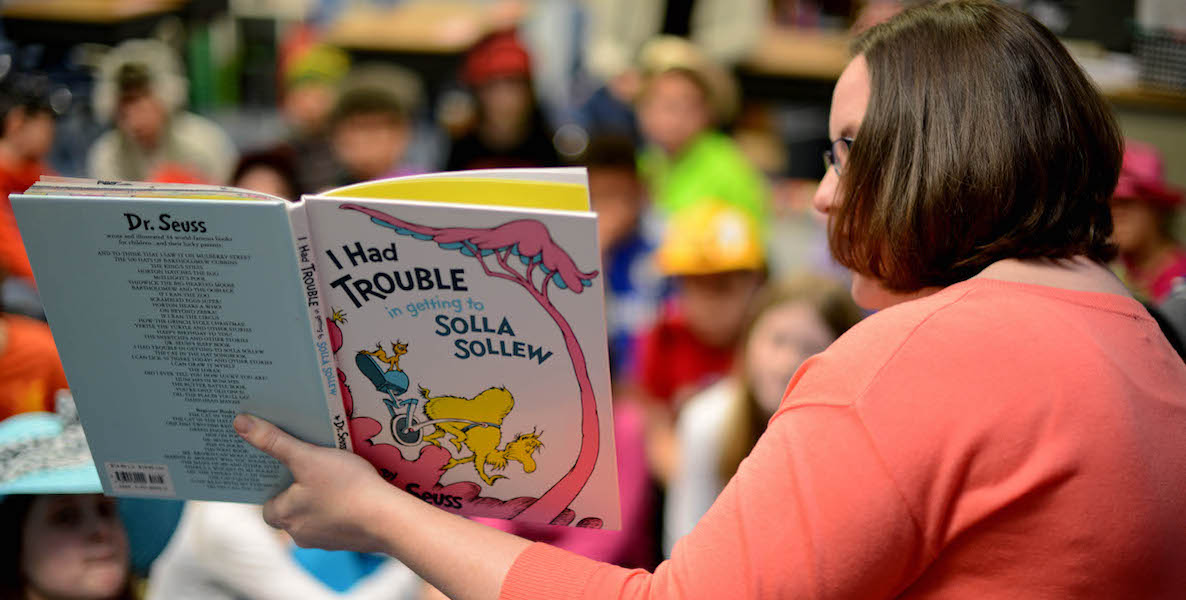

The Kenney response was reminiscent of the dismissive way the administration has handled critiques of the soda tax. But sober analysis of the pre-K program ought not to be confused with the political fight over its funding. Studies show that quality pre-K moves the needle on a city’s educational and long-term economic fronts. But the key word is “quality.” With further pre-K expansion on the horizon it would be unfortunate if our leaders let political gamesmanship prevent Philadelphia’s much-needed educational program from reaching its maximum potential.

Among the major concerns highlighted by Butkovitz were pre-K centers’ $102,000 in overbilling for students who were never enrolled, a lack of a written plan for future pre-K expansion, and the inclusion of soda tax revenues in the General Fund rather than a more transparent Special Revenue Fund. At one center, auditors found inconsistencies between what was written in city-approved inspections and what they could actually find in person, calling into question the cleanliness of the site and whether two out of three employees had received criminal background checks. The file that should’ve contained a background check and teaching certificate for one employee was missing at another site. There was also the revelation that nearly one out of five pre-K centers didn’t live up to “quality” standards set by the state.

Among the major concerns highlighted by Butkovitz were pre-K centers’ $102,000 in overbilling for students who were never enrolled, a lack of a written plan for future pre-K expansion, the inclusion of soda tax revenues in the General Fund rather than a more transparent Special Revenue Fund, and the revelation that nearly one out of five pre-K centers didn’t live up to “quality” standards set by the state.

There’s no consensus on the best form pre-K should take, and well-known programs like Head Start have been questioned. But Philadelphia leaders have determined the best route to quality pre-K is through providers with STAR ratings of 3 or 4, as determined by the Pennsylvania Department of Education under a system that evaluates the education of staffers, the learning environment, the abilities of a program’s leaders and family and community partnerships.

The city knew going in it wouldn’t have enough pre-K centers rated 3 or 4 if it wanted to enroll 2,000 students the first year, with a goal of 6,500 in five years. The infrastructure wasn’t there. When the pre-K program began last January, about 39 of the original 88 sites were rated 2 or lower. The Universal pre-K Commission expected these centers would “grow into quality” and reach a 3 or 4 STAR rating within 18 months. By early December of last year, according to the Controller’s report, 21 of the lower-rated centers had earned a 3 rating. Eighteen centers remain under 3, and Butkovitz cited a lack of a written policy for how to deal with centers that don’t reach the benchmark for “quality” by the end of the 18-month period.

Otis Hackney, the city’s Chief Education Officer, addressed the critique by writing ![]() to Butkovitz that “we intend to assess providers’ continued participation in PHLpreK on a case-by-case basis and will only continue to partner with those that have a demonstrated commitment to improving the quality of their program.” He wrote nothing of implementing a written policy or explicitly cutting ties with centers still at a 2 rating.

to Butkovitz that “we intend to assess providers’ continued participation in PHLpreK on a case-by-case basis and will only continue to partner with those that have a demonstrated commitment to improving the quality of their program.” He wrote nothing of implementing a written policy or explicitly cutting ties with centers still at a 2 rating.

In fact, rather than admit deficiencies or thoroughly explain plans in place to correct them, Hackney began most of his responses to the list of critiques with “This is incorrect.” He responded to the number of centers rated 2 or lower by writing the pre-K commission OK’d centers that were “growing into quality.” He didn’t directly address the alleged problems with background checks.

Butkovitz saw the responses as defensive and unproductive denials. “Overall they got pretty good grades,” he says. “I don’t understand why they took such pains to try to deny any of the imperfections in what was a new program.”

But the city’s response has evolved since the publication of the report. Sarah Peterson, communications director for the Mayor’s Office of Education, says via email that the city is working now to finalize a contract termination process by June. The Mayor’s Office responded to many other shortcomings by pointing at the soda industry, specifically a lawsuit headed for the state Supreme Court.

The American Beverage Association and several local businesses and individuals sued the city shortly after the tax passed in 2016. Judges ruled in favor of the city at the trial level and Commonwealth level. After a six-month wait, the Supreme Court said in late January it would hear the case, which means it could go on until this fall. Peterson says the lawsuit has prevented further expansion of pre-K and funding for technical assistance to lower-rated centers. So far, the city has provided about $800,000.

It expected to have $11.2 million in funds available for this assistance, which has included courses for program administrators and teachers and physical enhancements to classrooms. Various centers have gotten books, gardening kits, musical instruments and a sand and water table for games. The Mayor’s Office credits these offerings with helping increase the ratings of 22 pre-K centers.

The Kenney response to Butkovitz’s report was reminiscent of the dismissive way the administration has handled critiques of the soda tax. But sober analysis of the pre-K program ought not to be confused with the political fight over its funding.

Given the litigation, the decision to cap pre-K enrollment at 2,000 makes sense. Philadelphia wouldn’t want to commit to thousands of extra seats while the possibility of the Supreme Court nullifying the tax remains. But the lawsuit can’t be used to cover every issue with the pre-K rollout. How does a lawsuit hinder the preparation of a written plan for expansion? And if technical assistance is working, shouldn’t the city double down on the current centers in need? Philadelphia has already committed to enrolling students at these centers, and progress toward STAR ratings of 3 and 4 is vital to their success.

Rebecca Rhynhart, who became Controller in January after soundly defeating ![]() Butkovitz in the 2017 Democratic Primary, says she will “keep my eye” on the ratings of the pre-K providers at the end of the 2017-18 school year. She agrees with setting up a Special Revenue Fund for soda tax dollars to create more transparency.

Butkovitz in the 2017 Democratic Primary, says she will “keep my eye” on the ratings of the pre-K providers at the end of the 2017-18 school year. She agrees with setting up a Special Revenue Fund for soda tax dollars to create more transparency.

Of Butkovitz’s report, Rhynhart also says, “I think the genesis for that audit had to do more with the soda tax perhaps than the pre-K.” Indeed, Butkovitz had been attacking the soda tax for months, which makes him a less than ideal person to audit the program soda money is funding. And he is still “seriously exploring” that mayoral run for 2019. Yet he says a staff of professional auditors conducted the report with no agenda: “We call things as they are, not to support any preconceived position that I have…The Kenney administration has this sensitivity about contrarian views or contrarian evidence.”

You don’t have to be a Butkovitz supporter to concede that, generally, the M.O. of the Kenney administration has been to shut down any criticism of the soda tax, whether it’s Butkovitz’s findings, Pepsi claiming to lay off 80 to 100 workers because of the tax or ShopRite’s Jeff Brown saying he had to reduce workers’ hours. The administration’s reaction tends to be political, aimed to ensure support for the tax, which is here to stay barring an unlikely reversal from the Supreme Court of the lower courts’ decisions.

But even a broken watch is right twice a day, and sometimes a flawed or suspect messenger can deliver an important message. The administration needs to know when to separate the soda tax from the pre-K. The former involves a messy political battle where nobody wants to be proven wrong. The latter is purely about educating Philadelphia’s children, and it’s far more important to get that right.

Clarification: The full statement about the Special Revenue Fund from new City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart was as follows: “There’s one finding that the revenues should be kept in a Special Revenue Fund. I think that gets to the issue of transparency around soda tax dollars.”

Header photo: U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Kaylee Dubois