The job of urban school principal in a district like Philadelphia’s is almost absurdly overwhelming. Bill Griffin, principal of John Hancock Demonstration School in the Northeast, for example, is chief academic officer for nearly 750 elementary and middle school students. He’s also Hancock’s business manager, signing off on every expense; its human relations director, overseeing all aspects of training and evaluating his 100 or so staff members; its public outreach officer, meeting with parents, greeting students, reaching out to the district and community partners. At various times, Griffin is also security guard, secretary, trash remover and social worker.

“What we expect principals to bring to schools is completely and utterly an impossible business model,” says Griffin. “And in my nine years as a principal, it’s gotten even more difficult. More is expected from us than ever before.”

Ultimately, keeping the lights running and the bells ringing at his two school campuses every day is on Griffin. But to really succeed as a principal in Philadelphia requires a lot more than just getting through the school day. It requires what Tim Matheney, executive director of the Philadelphia Academy of School Leaders, calls “entrepreneurial leadership”: Those who have a vision for the school that they work to achieve within its walls, but who also make strong connections with the community outside of school. “In Philadelphia, that’s a key skill set,” Matheney says.

That’s the guiding principle of the Academy of School Leaders, a three year-old training program that is turning the best Philly principals into practical visionaries with the potential to drive change in a district that much needs it. Last week, School Leaders held its third week-long institute for 22 principals across school types—public, charter and religious, all with a significant portion of impoverished students. In total, the group has so far trained 62 principals in concepts that blend aspects of entrepreneurship and education—a way of looking at school leadership that upends the 20th Century model, and could be the key to academic success.

For principals, Matheney says, thinking and acting like an entrepreneur is the third strand of leadership skills needed to successfully turn around a school. First, principals need to be visionaries, with a school-specific set of goals that they infuse into every aspect of the school day—from how they use academic time, to how they spend recess. Second, they need to be collaborators, distributing responsibility for carrying out that vision to teachers and other staff members, particularly those who are “irreplaceable” to the mission.

This is not the 20th Century way of looking at school leadership, as the job of an academic. Instead, it acknowledges that principals are community leaders, whose schools are neighborhood hubs, providing food, emotional care, social services and education to children. That requires looking outside of the school walls and beyond District headquarters at 440 North Broad.

Principals as entrepreneurs take that vision and collaboration a step further, looking outside the school and the District for ways to accomplish their mission. There’s some good reason for that. Amidst the bureaucratic turmoil of the last several years, the District has mislaid thousands of textbooks in its basement, floundered on an at least $1 million art collection, disastrously flubbed the contract for substitute teachers and spent years unable to figure out how to negotiate a contract with regular teachers.

It’s clear that principals need to think differently. That can mean forming partnerships with community-based organizations and Friends Of groups, or advocating with the District for more staff or funds, or raising money from philanthropists and individuals—all with an eye towards a specific goal. “I met a principal in New Jersey who never met an innovation he didn’t like,” Matheney says. “But that doesn’t necessarily work. Everything in a school has to be aligned to a coherent vision. Entrepreneurship is really hard.”

School Leaders was started by philanthropist Joe Neubauer, former CEO of the Aramark Corporation, who had long been a supporter of the arts in Philadelphia. (He is currently chairman of the board of the Barnes Foundation, among other things.) In 2014, Neubauer started looking for a way he could significantly impact the state of K-12 education in Philadelphia, and turned to his fellow board members and colleagues at his alma mater, the University of Chicago (where he is also board chair). Their suggestion: Look at principals, a relatively small number of people whose influence on their communities goes way beyond the main office.

“It’s hard to get your arms around a city’s worth of students, or even teachers,” says Matheney, a former New Jersey high school principal and schools official, who Neubauer brought on in 2015. “There are about 400 principals in Philadelphia. You can get your hands around that.”

The Neubauer Fellows—as the carefully-selected group are called—are seasoned school leaders, with at least 10 years of education experience, and usually more like 20. They are chosen through a rigorous screening process that includes a written application, an interview, a video teaching exercise and often a school visit. That ensures the group that gathers every summer already collectively shares a vision of the basic elements required to operate a successful school in Philadelphia. “As a group, we all had a certain amount of tenacity, of never giving up,” says Griffin, a Neubauer Fellow since last summer.

In total, the group has so far trained 62 principals in concepts that blend aspects of entrepreneurship and education—a way of looking at school leadership that could be the key to academic success.

Matheney was a principal in South Brunswick High School in New Jersey for eight years before becoming that state’s Chief Intervention officer, overseeing 14 struggling districts. He recognized something else about this particular strata of school leaders: They are folks for whom ordinary professional development sessions are no longer effective. Midpoint in their careers, they are mentors themselves, training others; but they don’t receive much in the way of training that allows them to grow as leaders—something that can cause many to leave the profession all together. School Leaders is filling that gap, something the District has acknowledged with a $350,000 contract over the next two years. (The Neubauer Family Foundation has a multi-year commitment to School Leaders, and the William Penn Foundation has given $500,000 for a collaborative project with teams of teachers.)

Each School Leaders cohort starts their training with an intensive six-day summer institute that this year took principals through the different types of leadership. One day, a former Chicago charter school CEO led them on a vision-forming exercise; another, Canadian academic Joanne Quinn, talked to them about the best practice model of building coherence among school members; and a Chicago area superintendent offered tips on creating collaboration among teachers and staff. On the final day of the institute, principals heard from Opera Philadelphia’s David Devan, who in transforming his cultural organization over the last several years embodied all these principles.

At the end of the week, principals submit individual goals for their schools, and over the next several months, Matheney and his colleagues work with them to get there. “These are experienced principals, and we’re not telling them what to do,” Matheney says. “We want them thinking about context and identifying what their needs are and what they want to achieve. And then we ask how we can help.”

The Fellows will also meet for three more mini-institutes this school year, and for three to four dinners with business leaders, including Comcast’s Brian Roberts—past guests have also included Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia President and CEO Madeline Bell, and Police Commissioner Richard Ross—who will impart lessons on managing, inspiring and turning around complex organizations.

This is not the 20th Century way of looking at school leadership, as the job of an academic. Instead, it acknowledges that principals are community leaders, whose schools are neighborhood hubs, providing food, emotional care, social services and education to children. That requires looking outside of the school walls and beyond District headquarters at 440 North Broad Street, to community organizations, local businesses, philanthropies, nonprofits and anyone else who can offer a service or donate funds to create schools that are addressing 21st Century needs.

The Neubauer Foundation jumpstarts this lesson in a way that forces principals to take note: With a $12,500 matching grant they offer to any Fellow who can raise the same amount for a project that forwards their vision. At Hancock, Griffin used that money—along with funds raised by local unions, businesses and Councilman Allan Domb—to open a maker space in the middle school, part of his push to graduate students with skills applicable to their modern world. Griffin says the entrepreneurial leadership lessons gave him two things: Permission to think beyond the school as he had known it, and specific training in how to write grants for outside funding. He, in turn, passed that skill on to his staff, who now have a regular system for soliciting funds for projects. “I realized that if I want to make changes at my school, we have to stop looking within the district for help,” he says. “We have to look outside. Now my money is making more money because I have the tools to achieve it.”

It will take several years to measure quantitatively the real impact of the Philadelphia Academy of School Leaders; Matheney says it can take five to 10 years to change a school, especially one in which students have less outside support. But already, the group claims successes in one measure: Retention.

“We want our principals to think of themselves as important leaders in Philadelphia—because they are,” says Matheney. “We affect principals, who affect their schools, which affect their students and their communities.”

Nationally,Matheney says, 27 percent of principals leave urban schools every year. Of the Neubauer Fellows, only one principal has left the city of Philadelphia, to take a job in another district. Two others have taken promotions, one in the District and one in a charter company where they work. And Neubauer principals have also retained more of their own teachers than the norm. Of the “irreplaceable” teachers identified by Neubauer Fellows in the last year, Matheney says 90 percent have stayed at their schools.

“We want them to be attuned with the best of the best, and specifically train them on ways to keep their teachers motivated,” Matheney says. “If you have high quality teachers in a safe environment that is warm and welcoming, you are going to be able to boost student achievement. Some of the schools are the most challenging in the city, and our principals are still retaining them.”

In the end, all that matters is whether students are learning and being prepared to work when they finish school, whenever that is. And principals are not the only, or necessarily the biggest, reason individual students learn or don’t learn in a classroom. But they can also have an outsize influence on education in Philadelphia. So far, School Leaders has trained less than a quarter of the city’s principals. But many of those principals are leaders in their neighborhood networks, where they pass on some of what they have learned. They are all leading teams of teachers, future school leaders who are learning to think beyond the classroom. And they are all community leaders, in their school, neighborhoods and the city.

“We want our principals to think of themselves as important leaders in Philadelphia—because they are,” says Matheney. “We affect principals, who affect their schools, which affect their students and their communities. The longer they stay in their role, the more impact they have on student achievement.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Tim Matheney’s name. It also misstated the year the Philadelphia Academy of School Leaders started. It was 2014.

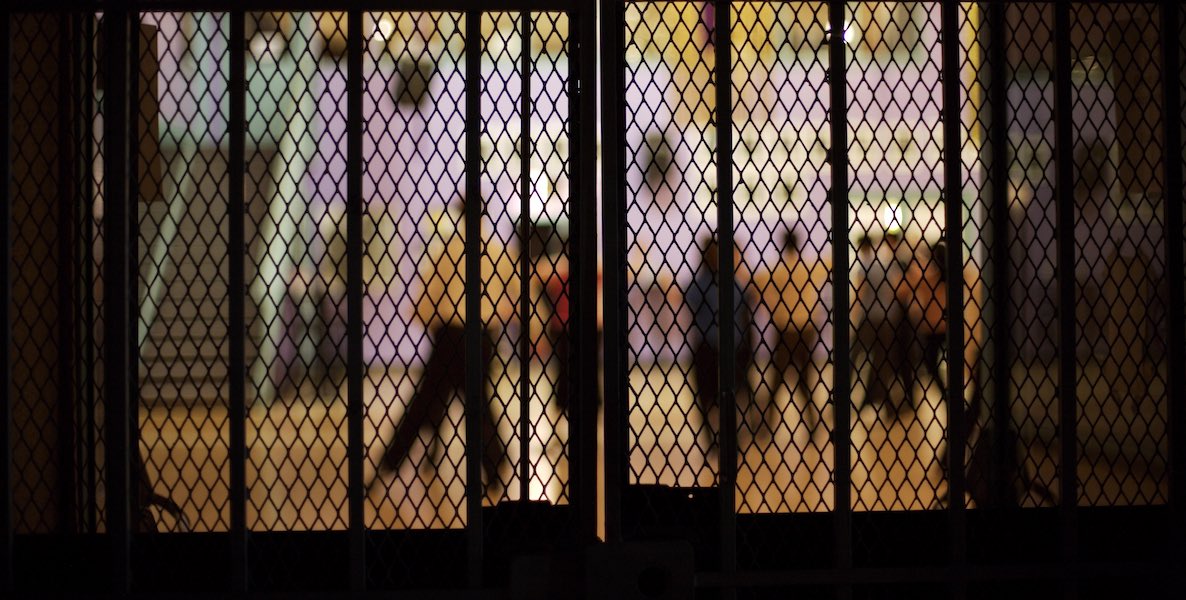

Header photo: Scott Spitzer Photography